Employment in India

Who is in India’s labour force, who is out of it, and what work people in the labour force do

India is the second largest labour market in the world with a little under 600 million people working or seeking work. In this section, we look at who is in India's labour force, who is out of it, and what work people in the labour force do.

Information on employment in India and most countries is gathered by asking people about the work they did in a recent time period through household surveys. Most data for India used here comes from the Periodic Labour Force Surveys, large nationally representative sample surveys, conducted by the Indian government, while international data comes from the International Labour Organisation. For a more detailed discussion on measuring employment and unemployment, see this piece from our Measurement vertical.

What is work?

The PLFS asks respondents about the work that they do. The question is open-ended, and trained enumerators convert their answers into a system of codes. This means that all work - including established professions like hawkers, teachers or construction workers - and new types of jobs - like being a driver through an aggregator app, or a food delivery person - are covered. It also means that both formal and informal employment are covered.

In economics, work covers activities that produce goods or services that are either consumed by the household or are sold in the market for a price.

In Indian and international labour statistics, most activities that produce goods for self-use as well as for sale are considered as productive work[1]. So a farmer growing vegetables for the household to eat constitutes work, as does her selling those vegetables in the market.

But in terms of services, only those activities that produce an output which can be sold are considered work[2]. So transporting the harvested vegetables to the market for sale is work, but cooking those vegetables for the household members to eat, or the feeding of children is not considered work.

Whether this unpaid care and domestic work that is mostly performed by women should be counted as productive work is a widely debated topic in labour economics[3].

Who is in India's labour force

India is a signatory to global conventions which prohibit children under the age of 15 from working[4]. There are close to one billion people above the age of 15 in India who can legally work[5].

This working age population can be divided in three broad categories from the lens of the labour market:

- Employed: those who are working

- Unemployed: those who are not currently working, but seek work or are available for work, and

- Not in the labour force: those who are neither working nor seeking work

The first two categories form the labour force. A little less than 600 million Indians, or six in ten working-age people, are in the labour force, while about 400 million working age Indians are out of the labour force[6].

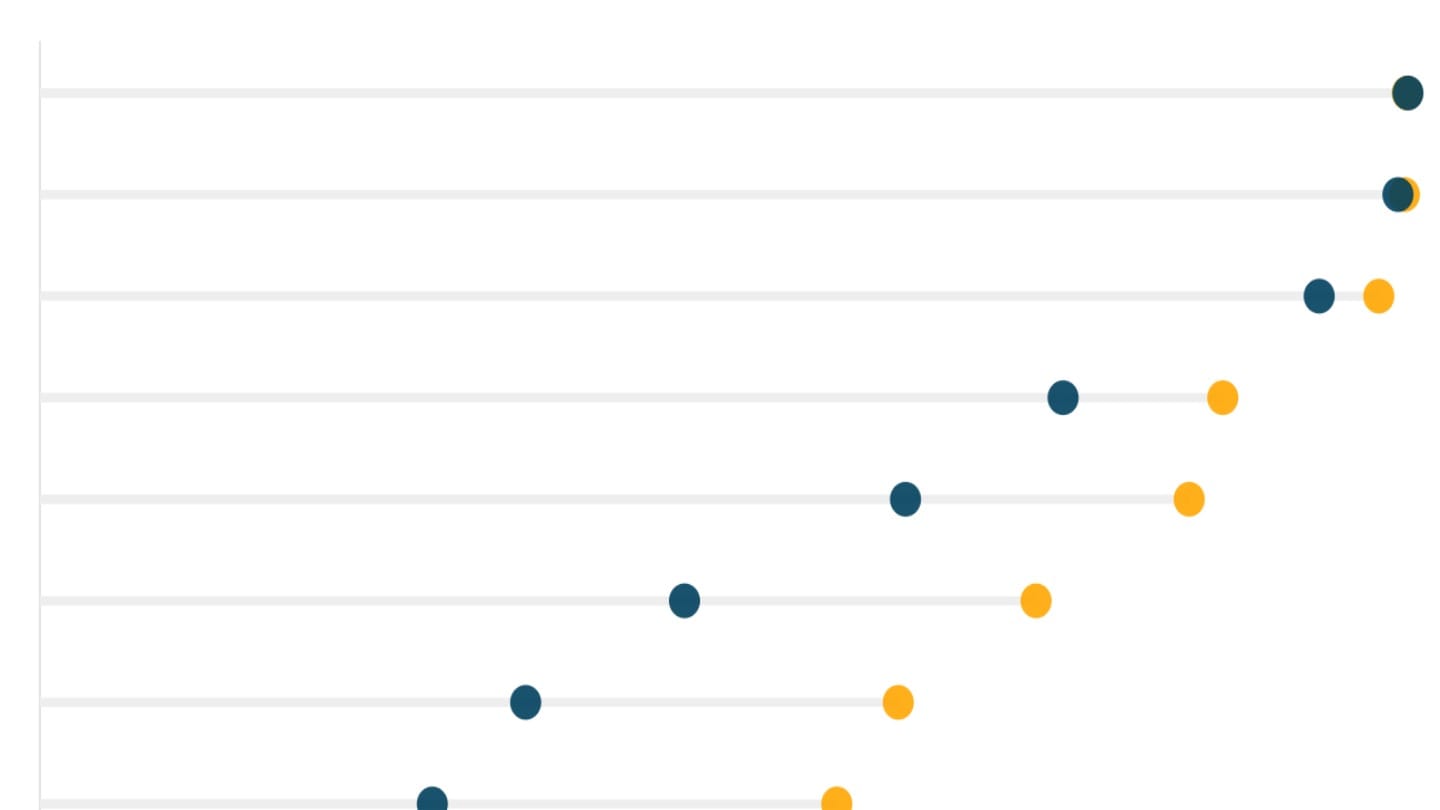

India's labour force participation rate - the share of the population that is in the labour force - is lower than that of South Asian peers such as Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, and other comparable middle income countries[7].

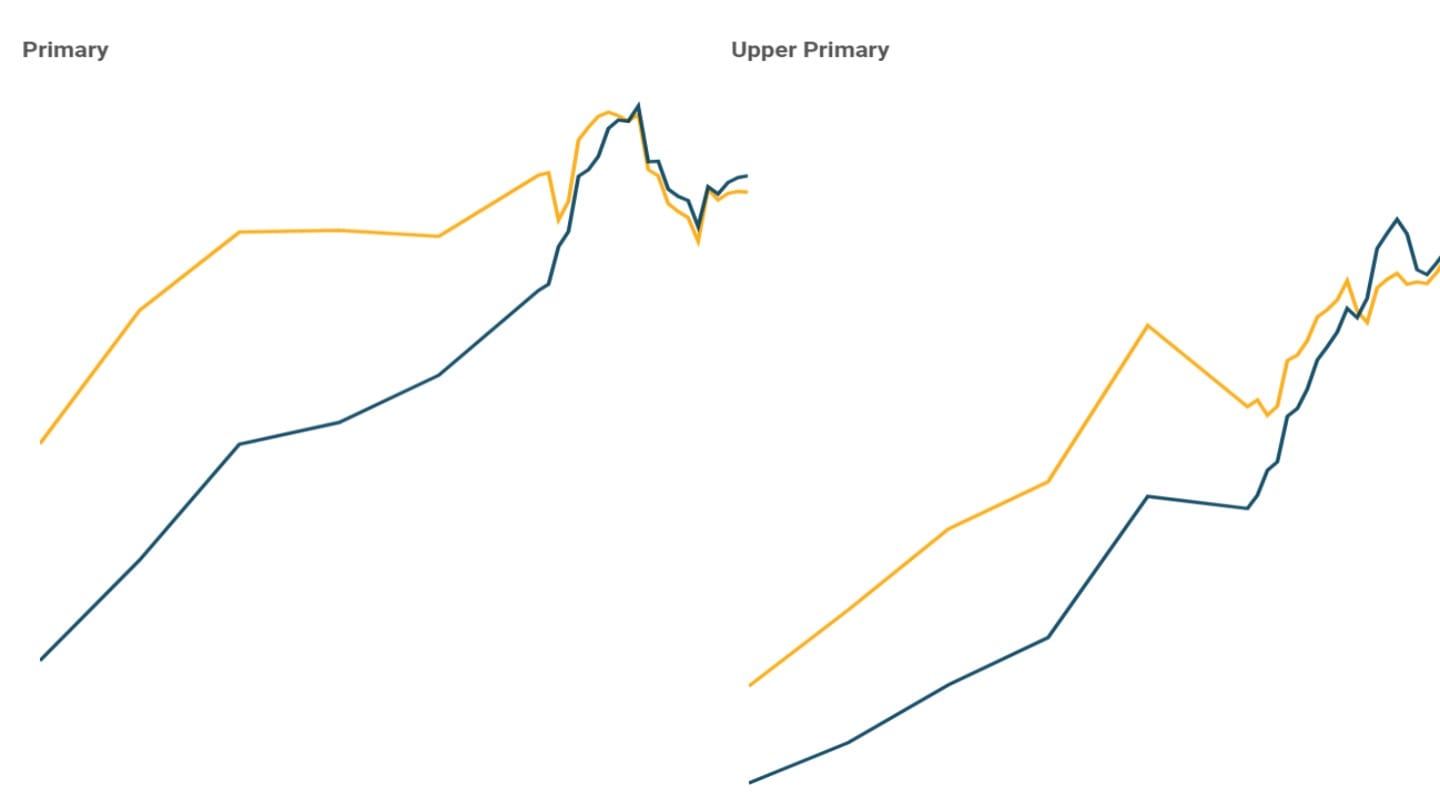

One part of the explanation for this is that more young people (aged 15-24) are now pursuing education than before[8]. But a larger part of the explanation is that while Indian men enter the labour force at rates comparable to other countries, female labour force participation in India lags far behind that of men - fewer than four in ten working age women in India enter the labour force as compared to eight in ten men[9].

While female labour force participation rates are lower than those of males in many parts of the world, this gap is particularly sharp in India. There are just 180 million women in India's labour force, compared to 380 million men.

Economic sectors

Of the 580 million people in India's labour force, around 560 million are currently working. The remaining 20 million persons in India's labour force are unemployed (see section below).

In economics and Indian and international statistics, the economy is understood to be composed of three major sectors - agriculture, industry and services. In this categorisation, industry includes construction and manufacturing, in addition to utilities and mining. Services include trade, hospitality, transport, communications, real estate, financial services, professional services, public administration, defence, and other services.

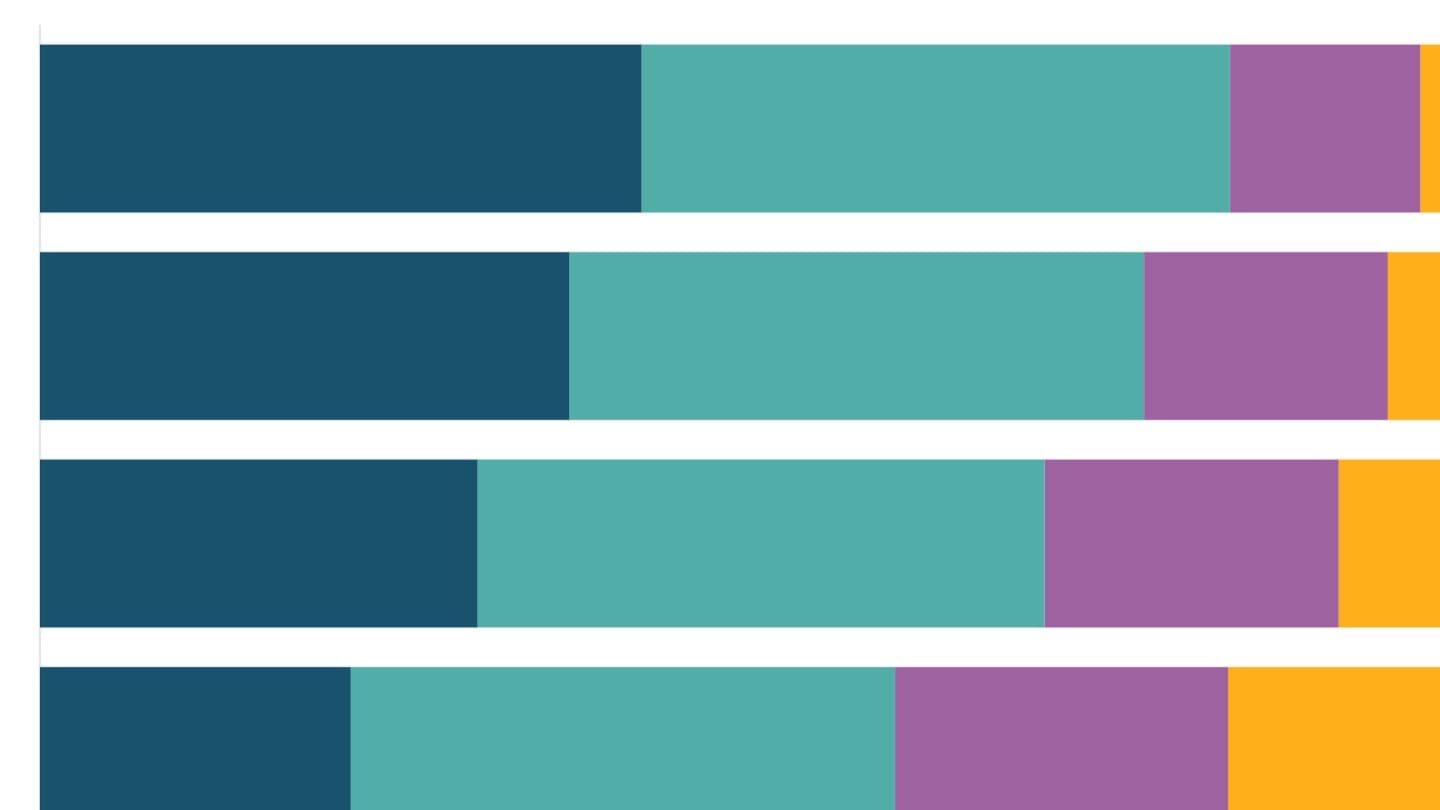

Agriculture employs just under half of India's workers or 260 million people, while industry employs 140 million and services 160 million people[10].

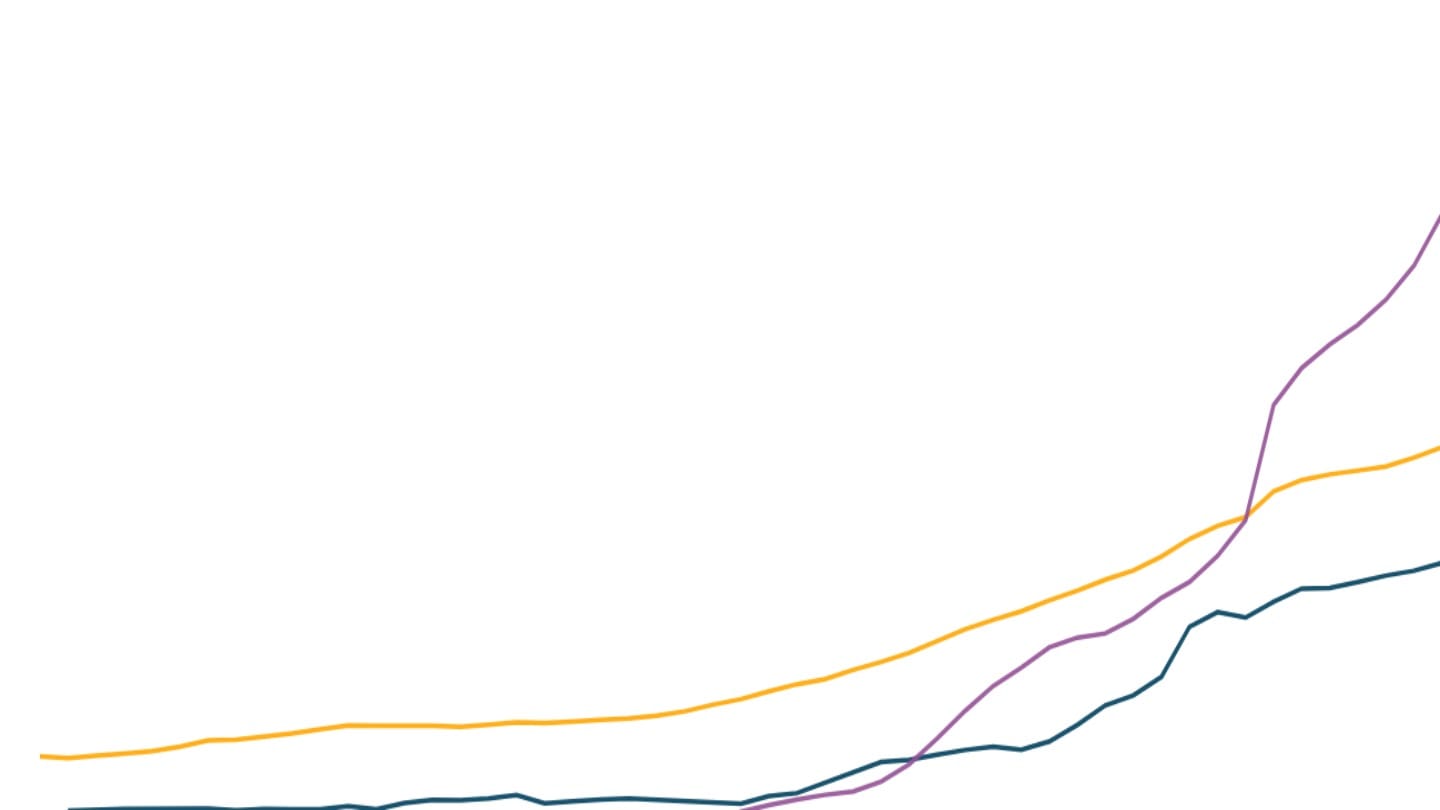

Over the last 50 years, there has been a significant change in the economic sectors that Indians work in, a change that is in line with the economic transformation that is expected when a developing country grows and industrialises. While agriculture still dominates, its share in total employment fell from three-quarters in the 1970s to less than half as of 2023.

The share of agriculture in Indian employment is still much higher than in comparable middle-income countries - around one in four in China and Vietnam, for instance[11]. Agriculture dominates in all states, even the most industrialised ones. For instance, Maharashtra and Karnataka have 40% of the jobs in information technology and 30% of jobs in financial services. Yet, nearly half of the workers in these states are in agriculture.

Those who moved out of agriculture entered industry and the services sector. Within industry, construction now employs 75 million people, more than the 65 million workers who are in manufacturing[12]. In the services sector, trade and hotels have been the biggest gainers and now employ 70 million people[13].

Types of workers

In labour studies, the nature of people's work is understood in three broad categories - salaried, casual and self-employed.

Salaried workers who work on a regular monthly payment basis account for around one in five Indian workers or 120 million people. In urban India, half of all jobs are now salaried and are concentrated in manufacturing, education, health, trade, and technology sectors.

Salaried jobs are the mainstay in advanced economies, but developing countries generally have a low and growing share. At 20%, the share of salaried jobs in India is low compared to 55% in China, 58% in Sri Lanka, and more than 90% in the US[14]. This share has remained unchanged for more than a decade.

Education raises the chances of a salaried job - among illiterate workers, only 6% are in salaried jobs, compared to 57% among workers who have diplomas or graduate degrees. Those with technical certifications are more likely to be in salaried jobs than those without.

But the meaning of a salaried job is not universal, and all salaried jobs do not have similar benefits. Only 42% of Indian salaried workers have a written official contract, 53% have eligibility for paid leave, and 44% have at least one social security benefit among gratuity, provident fund and healthcare.

Casual workers account for another one in five Indian workers or close to 120 million people. A casual worker works on someone else's farm or non-farm enterprise and receives daily or periodic wages. Construction in particular is dominated by casual workers.

The majority of Indian workers, or three in five, are self-employed. Agriculture is dominated by self-employment in rural areas, while the self-employed in urban areas might run small stores that sell food products, or could be tailors and drivers.

Public and private employment

Only about 6% of Indian workers work in the public sector. The public sector includes government departments, public sector enterprises, and autonomous organisations funded by the government. The public sector has a higher share in total employment in advanced economies compared to developing ones,

Most of the government jobs are in schools, in railways and public sector banks, in government-funded road and other construction projects, power and water supply utilities. Rural health workers and panchayat officials also form a part of rural government jobs.

Another 6% work for formal private companies. Within this small slice, half of India's private sector jobs are in manufacturing, while information technology has the next biggest share.

But, the majority of Indians work in informal enterprises, which are unregistered enterprises run at the household-level[15]. Many developing economies have a high share of informal workers, as opposed to advanced economies.

Unemployment

To measure the unemployment rate, workers are asked how long they worked during the last year. A person who worked for at least 30 days in the preceding 365 days is considered as employed, while a person who was looking for work or was available to work but did not work for even 30 days in the preceding 365 days is counted as unemployed[16].

Roughly 20 million Indians want work but cannot find it, meaning that they are unemployed. This puts India's India's unemployment rate - the share of unemployed among 580 million Indians in the labour force - at 3.2% (as of 2022-23)[17]. In urban areas, it was substantially higher at 5.4%.

The unemployment rate in India is higher among the better educated. In low-income countries, skilled jobs may be scarce and there could be a mismatch between skills and jobs. In addition, the better educated can afford to stay unemployed for longer, and might hold out for a suitable job[18]. While less than 1% of Indians educated up to primary level are unemployed, more than 13% of those with graduate degree or above are jobless.

Young Indians who are relatively newer entrants to the labour force face higher joblessness in India compared to experienced workers beyond the age of 34. Unemployment rates were below 1% for those above 35 but above 7% for youth (between the ages of 15 and 34) from 2018 to 2023.

While the unemployment rate is a crucial metric to understand economic trends in developed countries, it does not always fully capture the ability of developing countries to adequately employ most people. In the absence of unemployment insurance systems or social safety nets, most people of working age in poorer countries engage in some form of economic activity, even if it is inadequate[19].

[1] This definition follows from the System of National Accounts (2008), an internationally accepted statistical framework that is also used to define labour force and employment in PLFS and all NSS surveys on employment.

[2] Indian labour statistics have additional restrictions in their definition of work. The methodology of PLFS includes only the production of primary goods (the output from agriculture, mining, and allied activities) for self-consumption and the production of fixed assets for own-use such as a house inside the definition work. All other goods and all services (such as cooking food and childcare) fall outside the purview of work in the Indian framework of labour statistics.

[3] See work on this topic by ILO, OECD and UN Women

[4] India is a signatory to the International Labour Organisation's Minimum Age Convention, 1973, and Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999. According to these conventions, a person above the age of 15 can work, except in hazardous industries, for which they must be above the age of 18

[5] Using 2011 Census data, the National Commission on Population produced population estimates up to 2036 using assumptions about fertility, mortality and migration pathways. Since the 2021 Census has not yet been conducted, DFI and other research organisations use these government estimates for population

[6] All data in this piece is from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (2022-23) conducted by the National Statistical Office, unless stated otherwise

[7] The World Bank categorises countries into income groups based on their per capita income.

[8] Data based on EUS 1999-2000 and PLFS 2022-2023 shows that the proportion of 15-24 year-olds who say that their main annual activity is education has jumped from 27% in 2000 to 49% in 2023.

[9] Periodic Labour Force Survey (2022-23), National Statistical Office

[10] Absolute numbers have been rounded off to the nearest 10.

[11] Data accessed from World Bank World Development Indicators, based on modelled estimates by ILO

[12] The economist Dani Rodrik of Harvard University finds that countries like India are reaching peak industrialisation in terms of employment and output at much lower levels of income compared to the early industrialisers. Industrialization peaked in Western European countries such as Britain, Sweden, and Italy at income levels of around $14,000 per capita (in 1990 dollars), while India and many sub‐Saharan African countries appear to have already reached their peak manufacturing employment shares at income levels of $700 per capita. Rodrik called this "premature deindustrialisation" in his 2015 paper and suggests that it has potentially important economic and political implications

[13] Absolute numbers have been rounded off to the nearest 5.

[14] Share of "wage and salaried workers" in total employment as modelled by International Labour Organisation, and compiled by World Bank's World Development Indicators

[15] In the PLFS, informal sector enterprises are defined as unincorporated enterprises owned by households, (proprietary and partnership enterprises including the informal producers' cooperatives)

[16] In Indian labour statistics, the reference period most commonly used to understand employment is the preceding 365 days. Employment during this period (usual status) is a combination of principal status (those who worked or sought work for a relatively long part of the last 365 days), and subsidiary status (persons from the remaining population who had worked for at least 30 days during the last 365 days). Taken together, anyone who worked for more than 30 days in the preceding 365 days will be classified as a worker. The unemployed, then, will be those who sought work or were available for work but did not work for more than 30 days.

[17] This is the current latest official Indian estimate of the unemployment rate

[18] "Education pays off but you have to be patient," 2020, ILO

[19] As described by the ILO in its Labour statistics overview