Measuring malaria

Accurately estimating the incidence and mortality from diseases in India, including malaria, is challenging. We lay out the available data sources and explain our reasons behind using selected sources.

There is a significant lack of reliable and consistent data on malaria cases and deaths in India. While capturing direct estimates is challenging, modelled estimates can also be imprecise.

Malaria incidence is reported by the National Centre for Vector Borne Diseases Control (NCVBDC) and estimated by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation's (IHME) Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study. Mortality data comes from the Medical Certification of Cause of Death (MCCD) system and the Sample Registration System (SRS) Cause of Death (CoD) survey. Each source has unique methodologies, strengths and limitations.

Incidence

In the context of diseases, 'incidence' means the number of new cases registered, reported or estimated in a year.

The National Centre for Vector Borne Diseases Control (NCVBDC) under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), manages malaria surveillance and elimination programmes in India. Its reports are based on both passive surveillance (cases reported at health facilities) and active surveillance (targeted blood sampling in high-risk areas).[1] Diagnostic methods such as microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) are conducted by health workers, including Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs).[2]

The only other source of malaria incidence data is the IHME's Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study. For India, the study combines data from diverse sources, including government registries, surveys like DHS, entomological studies (primarily data and studies published on Malaria Atlas Project) and monthly reports from the Health Management Information System (HMIS). Using statistical models and covariates like climate and population density, it provides incidence estimates. The limitation of this source lies in its dependence on secondary data and uncertainties arising from assumptions used in statistical modeling.

The NCVBDC estimates are by the Indian government's admission under-reported. This discrepancy arises from incomplete reporting from the private healthcare sector and poor surveillance in remote, forested areas where logistical barriers and reliance on passive reporting miss numerous cases.[3]

For example, in 2020, NCVBDC reported 190,000 malaria cases, whereas modelled estimates from the IHME suggest close to 3.2 million cases - about 17x higher.

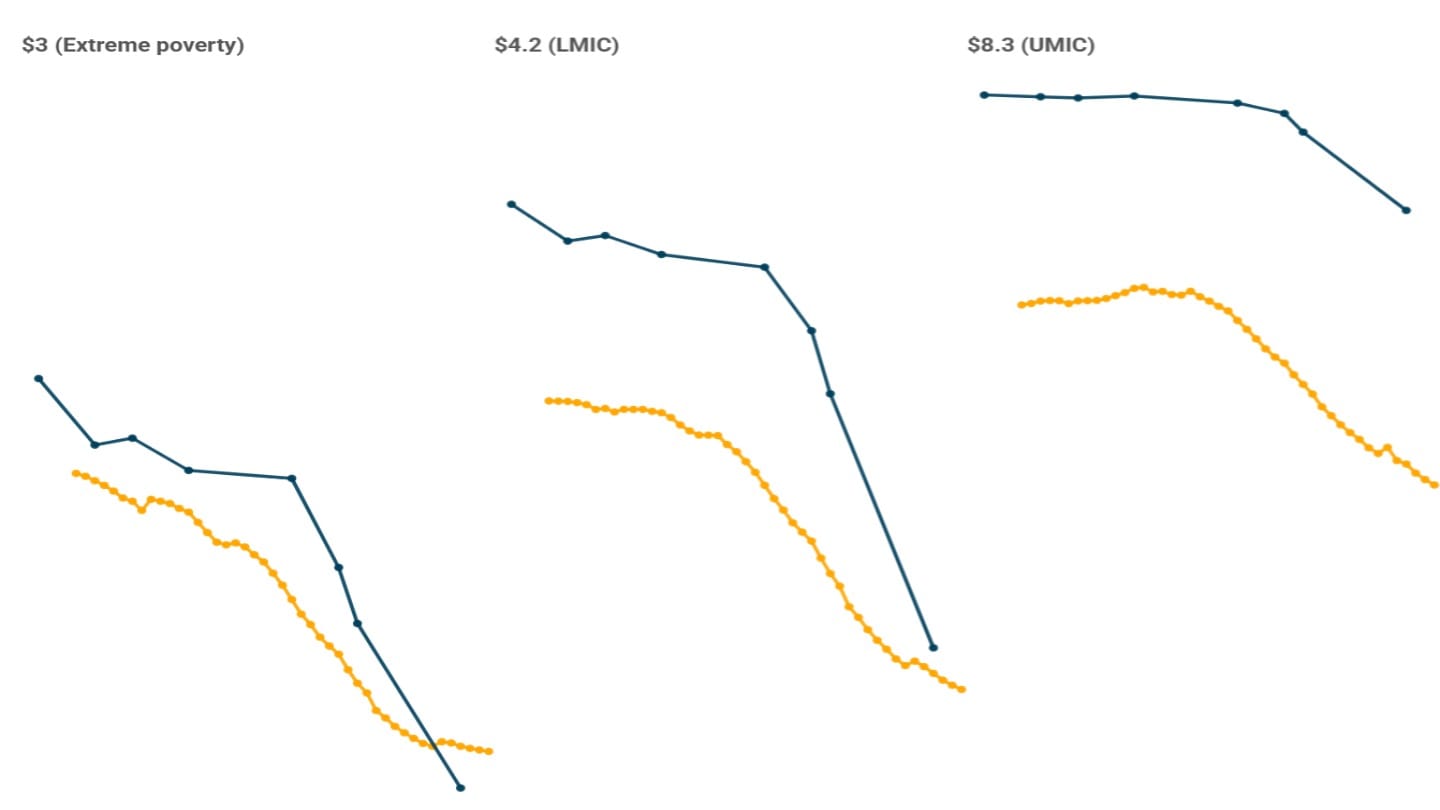

Both estimates from the NCVBDC as well as the IHME indicate a decline in incidence over time; however the burden of disease remains vastly different between the two datasets. As a result, we use the IHME estimates for incidence of disease.

Mortality

Accurate numbers of deaths from malaria are even more challenging to produce.

The most direct way to calculate the number of deaths from malaria would have been if the death of every Indian was medically certified. In India, the Medical Certification of Cause of Death (MCCD) system documents causes of death using standardised medical certifications provided by medical practitioners after a death. The consolidated report provides mortality data, helping identify disease patterns, allocate resources, and monitor health interventions effectively.

However, the dataset faces significant challenges, especially in rural areas where many deaths go unrecorded due to limited healthcare access and inadequate diagnostic tools. Only 22% of registered deaths in India are medically certified, with significant variation among states - from over 40% in Tamil Nadu to just 5%-10% in Bihar and Jharkhand.[4] This underreporting affects the accurate assessments of mortality trends, particularly in high-burden malaria states where medical certification rates are among the lowest. In 2022, the MCCD reported 1,265 deaths from malaria.

NCVBDC mortality data is limited by the same underreporting challenges affecting its case data. For instance, in 2022, it recorded only 83 malaria deaths, significantly lower than all other estimates.

To address this gap in cause of death data, India has been conducting the Sample Registration System (SRS) Cause of Death Survey since the 1960s. It is a national survey designed to estimate vital statistics, including causes of death. The 2021-23 (most recent) survey sampled 8.8 million people from about 4,000 urban and 5,000 rural units, representing India's diverse population.[5] For deaths recorded in sample areas, verbal autopsies (VA) are conducted - field workers interview family members about symptoms, medical history and death circumstances. Physicians then assign causes of death using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), including malaria codes (B50-B54).[6]

The SRS provides only the share (percentage) of deaths by gender and age group that can be attributed to a particular cause. We apply these percentages to the estimated total annual deaths to generate estimates of the absolute numbers of deaths from malaria. For years after 2011, total deaths are calculated by applying mortality rates from the SRS annual statistical report to the Census 2011 population projections[7], while for 2005 they are derived through geometric interpolation between the 2001 and 2011 census data.

IHME, through its GBD study, uses statistical models that account for underreporting and misclassification, offering broader estimates of malaria mortality. The primary data sources include government registries and providers like Institute of Health Systems (India), Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and State Bureau of Health Intelligence & Vital Statistics. However, it relies heavily on modelling. The dataset also provides upper and lower values of mortality and incidence estimates or the confidence interval. This indicates the range within which the true value is likely to fall. These intervals are crucial for understanding the reliability of the estimates and comparing trends across regions or time.

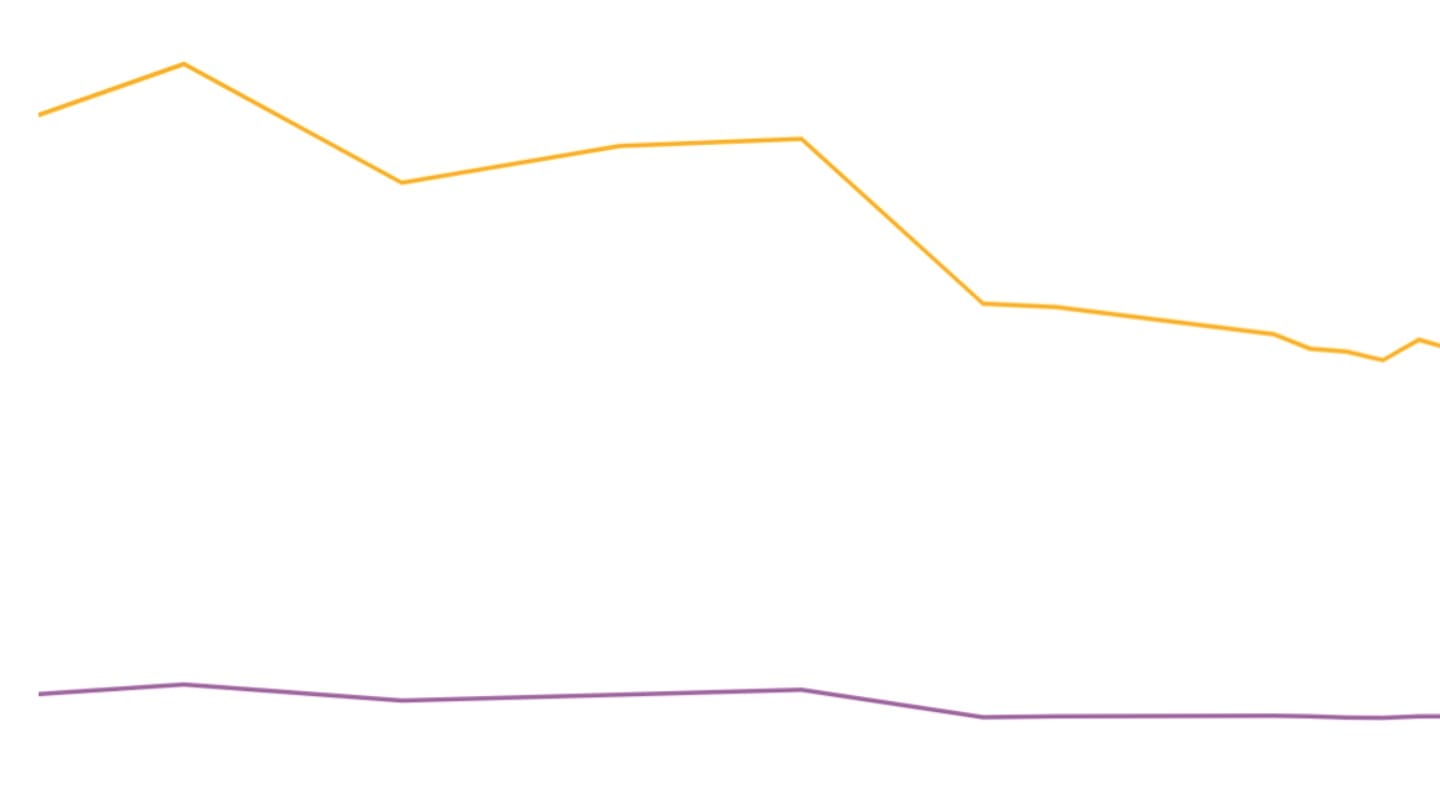

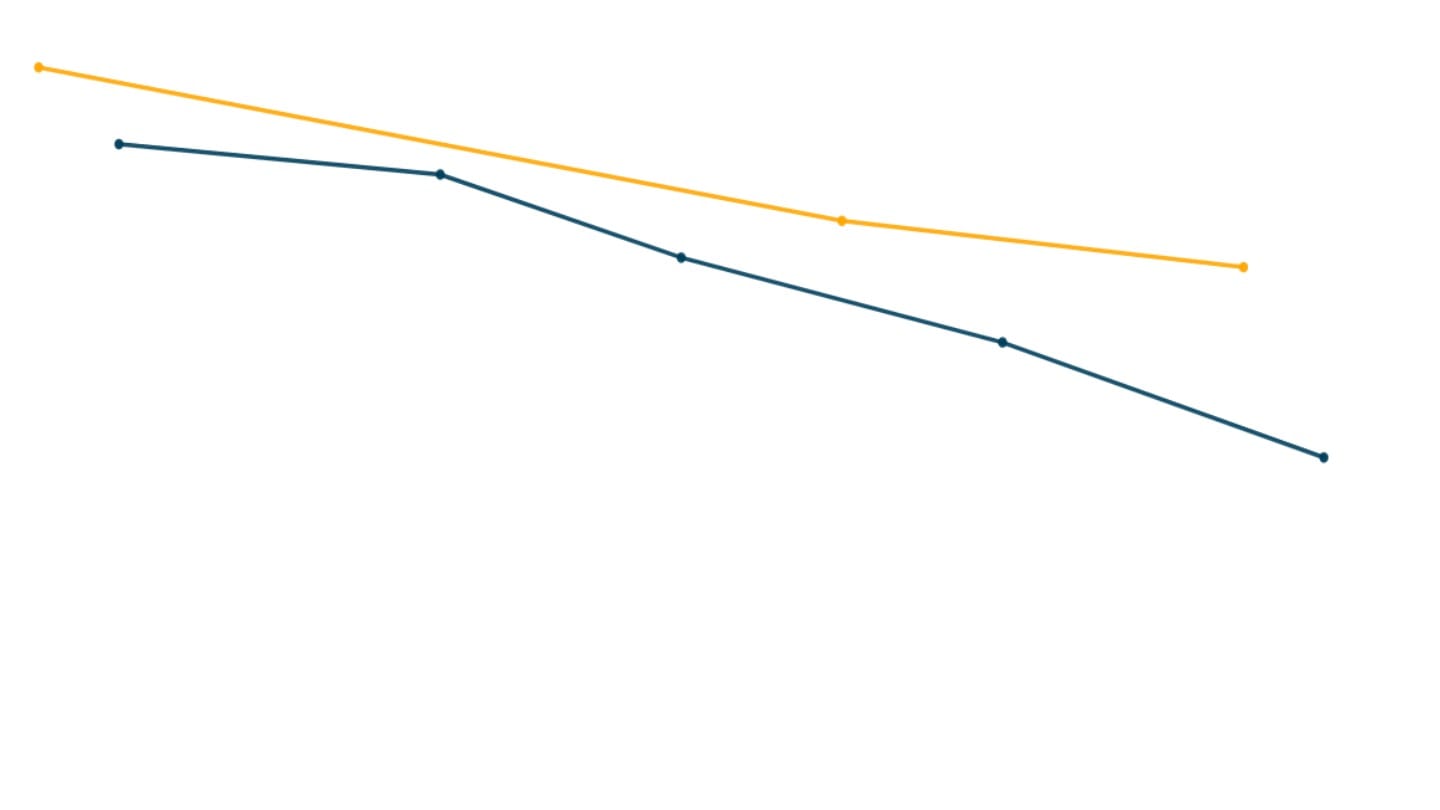

If we compare the three data sources for years in which all three report data, we find that administrative data continues to report far fewer deaths relative to the other sources. However, the gap between IHME and SRS estimates of malaria mortality has narrowed over time, alongside an overall decline in malaria deaths. In 2005 and 2012, SRS figures were over four times that of IHME's, but by 2020 the difference reduced to less than double.[8]

As a result, we use the SRS, a direct survey of a large sample of households, for estimates of mortality from disease for this piece. Since the SRS does not offer a state-wise breakdown of deaths, we turn to the IHME GBD study for state-level mortality data, despite its limitations.

[1] Strategic Action Plan for Malaria Control in India 2012-17.

[2] National Centre for Vector Borne Diseases Control (NCVBDC) reporting format.

[3] Strategic Action Plan for Malaria Control in India 2012-17.

[4] Report on Medical Certification of Cause of Death, 2022.

[5] Sample Registration System - Cause of Death in India, 2021-23.

[6] Protozoal diseases, ICD 10 Data.

[7] Census 2011 Population Projection for India and States, 2011-2036.

[8] We use 2020 IHME data, even though estimates are available up to 2021. Since IHME produces modelled estimates, the pandemic may have affected their accuracy, because the confidence interval for 2021 is considerably wide. For this reason, we have not used the 2021 data.