Childhood immunisation

Vaccines have played an essential role in reducing infant mortality in India. In this piece, we look at the vaccines currently given to children in India, their coverage, and identify gaps in the immunisation programme.

Childhood vaccination is a cornerstone of India's public health programme. India provides free of cost immunisation against 12 vaccine-preventable diseases under its Universal Immunization Programme (UIP), including vaccines that prevent poliomyelitis, tuberculosis, rotavirus diarrhoea and measles. Three in four children aged one year were fully vaccinated by 2021, the most recent year for which data is available.

India's immunisation progress

Vaccination is a crucial milestone in human history. Before vaccines, outbreaks of plagues and epidemics played a major role in shaping societies, often leading to widespread illness and death. The first vaccine, developed against smallpox in 1798, marked the beginning of modern immunisation. Since then, vaccination has become one of the most cost-effective interventions in medical science, contributing significantly to the global decline in mortality.[1]

The smallpox vaccine reached the Indian subcontinent as early as 1802, although the coverage was very limited initially. After independence in 1947, the government of India took steps to build a structured public immunisation system, starting with the Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) vaccine in 1948 against tuberculosis.[2]

The launch of the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) in 1978, and its evolution into the Universal Immunization Programme (UIP) in 1985, marked a turning point for childhood immunisation in India.[3] Under UIP currently, immunisation is provided free of cost against 12 vaccine-preventable diseases; nationally against 11 diseases, and sub-nationally against one disease. These diseases include poliomyelitis, tuberculosis, rotavirus diarrhoea and measles.

India has not only added new vaccines to the UIP in recent years, but has also replaced older ones with more advanced vaccines. For instance, the Diphtheria, Pertussis and Tetanus (DPT), hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccines have been combined into a single pentavalent vaccine. Similarly, following the eradication of wild polio in 2014, India has introduced inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) to address the rare risk of vaccine-derived polio, and will gradually phase out the oral polio vaccine (OPV) which helped achieve this milestone.[4]

Most vaccines are scheduled within the first 12 to 18 months of life because they are most effective when given before a child is exposed to the germs they are designed to protect against.[5] The UIP schedules most primary vaccine doses from birth through the first year of life, followed by booster doses in the second year. Additional booster doses are recommended later in life, along with specific vaccinations for pregnant women.

Do all children in India now get vaccinated?

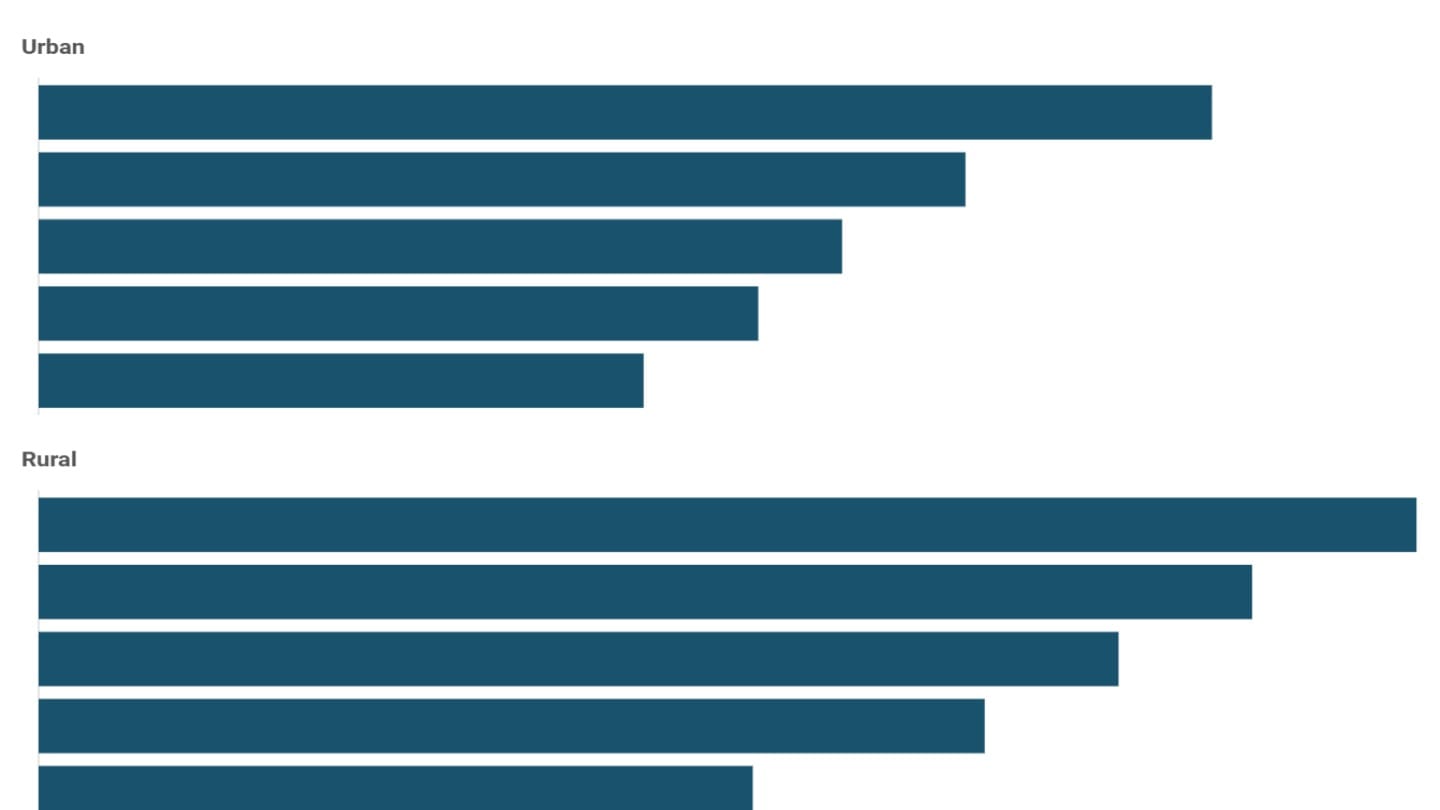

Three in four children aged one year were fully vaccinated by 2021, the most recent year for which data is available.[6] Coverage is slightly higher in rural areas, where around 77% of one-year-olds are fully vaccinated. Only about 4% of children aged one have not received any vaccination at all.

By other definitions as well, the number of children who have not received any vaccines is low. 'Zero-dose children' is a term used as a measure of lack of access to routine immunisation services. It is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as children who have not received the first dose of the DPT vaccine, since this is included in most national immunisation programmes and is one of the first vaccines given across countries.[7] The share of zero-dose children is about 7% overall in India.

Differences in vaccination coverage across wealth groups do exist, with about eight in ten children from the richest households fully vaccinated, compared to around seven in ten among the poorest.

Yet, this gap between the richest and poorest households is smaller than for many other health indicators. This is an important and somewhat unique feature of immunisation. Unlike most health outcomes, vaccination is only effective if a large share of the population is covered. It is not just an individual benefit but a community one, where protection depends on reaching as many children as possible.[8]

How has coverage changed over time?

Vaccination coverage has improved sharply over time, especially in rural India. In 1993, fewer than one in three rural children were fully vaccinated.[9] By 2021, this increased to over three in four children.

During this period, the share of zero-dose children in rural areas also dropped significantly, from about four in ten to less than one in ten, driving the overall drop in such children in the country.

India in global context

India's progress is also notable in an international context. Over the years, coverage for major vaccines such as DPT and measles has increased faster in India than in the world on average.[10]

This progress has taken place within a broader global framework. Most countries run public immunisation programmes guided by recommendations from the World Health Organization. While the WHO issues guidance as new vaccines are developed, the decision to add a vaccine to a national immunisation programme is made by individual countries, based on factors such as burden of the disease, availability and effectiveness of the vaccine, and the strength of the public health system.[11] In India, these decisions are taken by the National Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (NTAGI).[12]

Regional differences in vaccine coverage

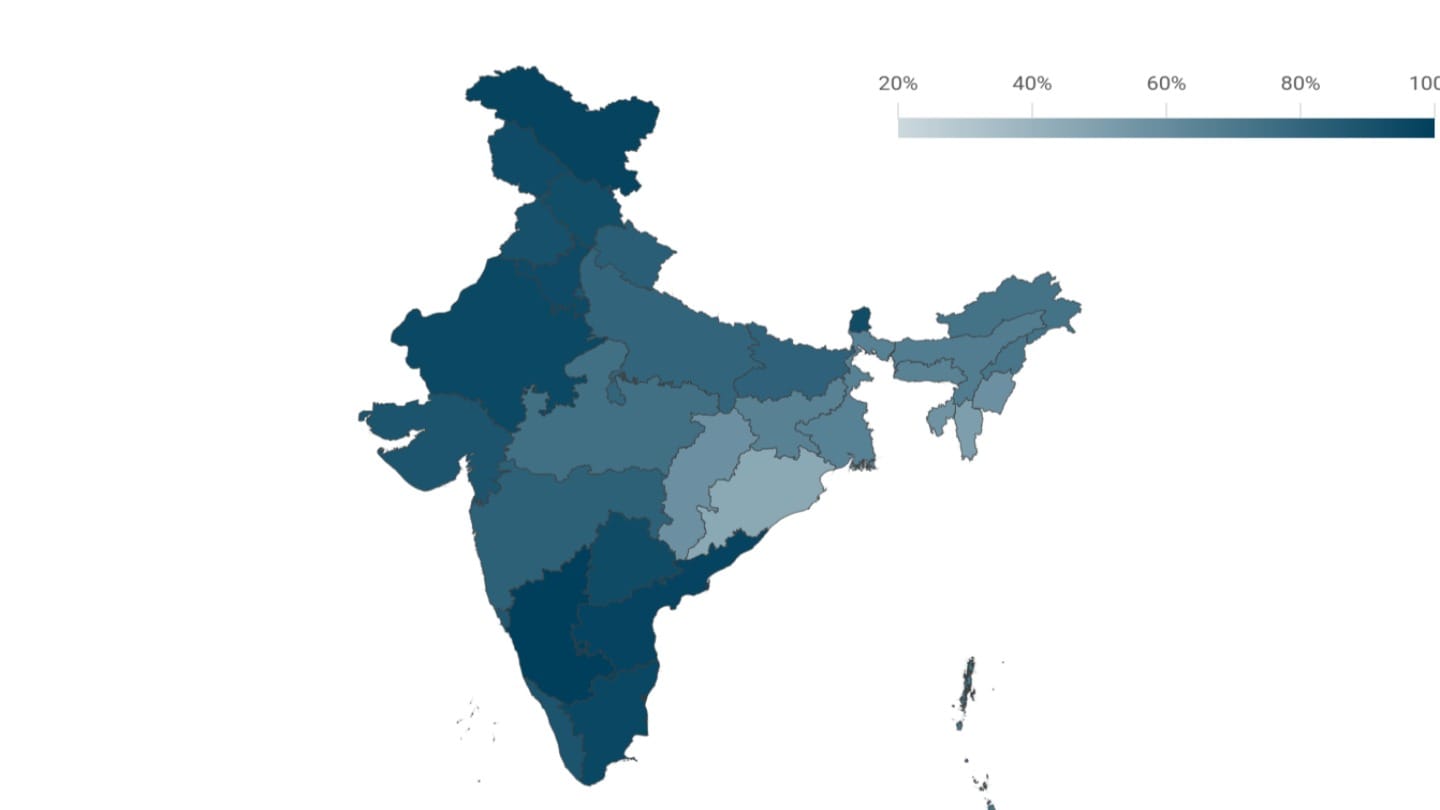

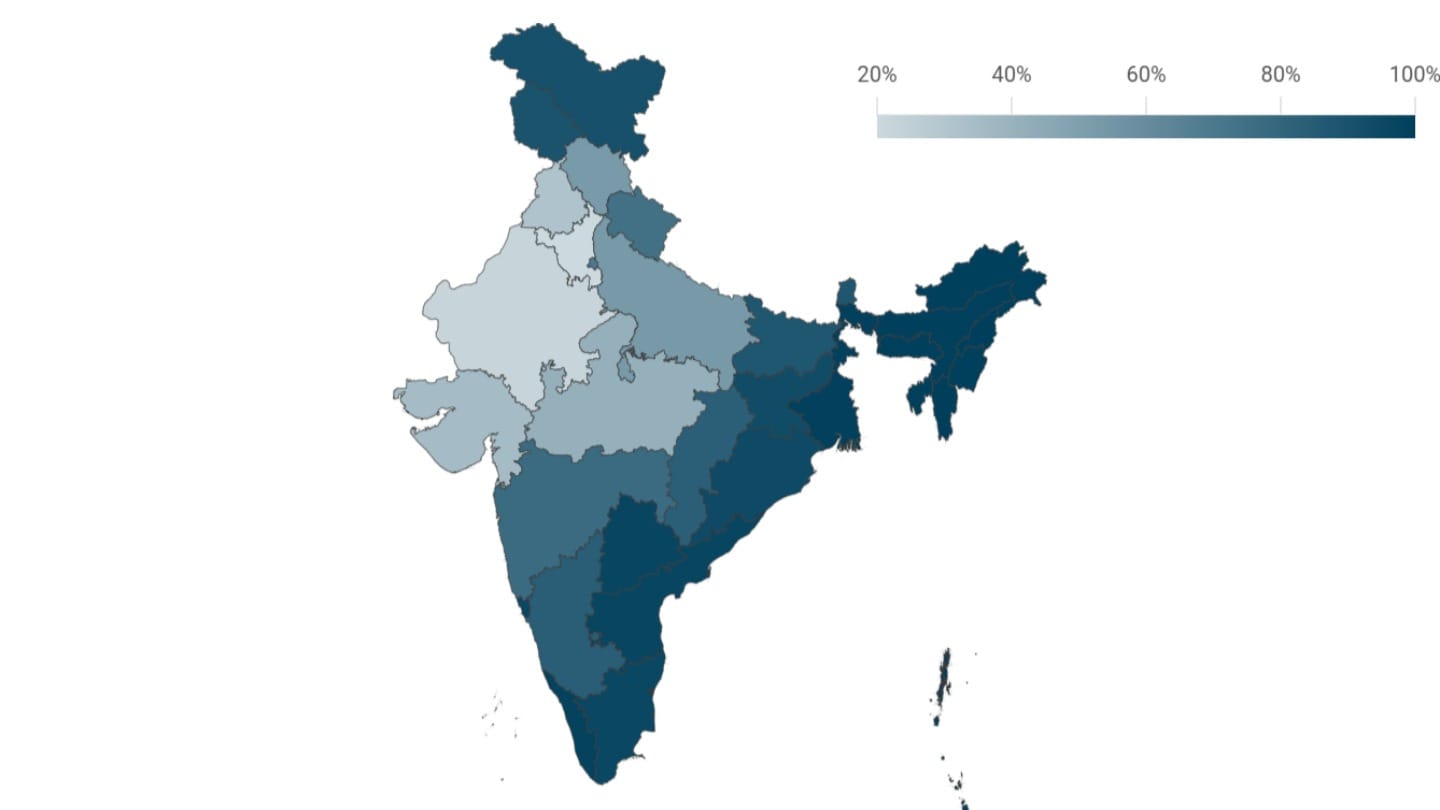

Despite national gains, there are large differences between states. In 2021, Odisha had the highest share of fully vaccinated children, with coverage well above the national average. Other states where close to nine in ten children are fully vaccinated include West Bengal, Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu. In contrast, several north-eastern states record some of the lowest vaccination coverage in the country.

Which states have improved the fastest?

Some states have improved faster than others. States like Odisha and Rajasthan made steady gains and overtook traditionally high-performing states like Kerala by 2021. At the same time, some states saw recent stagnation or a decline in coverage, in the period following the COVID-19 pandemic, when regular public health services were disrupted.

Vaccination schedule and coverage

Within six weeks of birth

India's childhood immunisation programme includes a set of vaccines given from birth to protect children from several serious diseases. Coverage is the highest for vaccines given earliest, and reduces for those scheduled later in a child's life. At birth, children receive the BCG vaccine, a birth dose of hepatitis B, and the oral polio vaccine.[13] Since BCG is given immediately after birth in the hospital, it has the highest coverage of all vaccines, at around 95%.

At six weeks of age, children begin a new vaccine series along with the first booster for polio. This includes the pentavalent vaccine, which protects against five diseases - diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, hepatitis B, and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infections. Before 2015, these were given through three separate vaccines: DPT for diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus, and separate vaccines for hepatitis B and Hib.[14]

About 93% of children aged one have received the first dose of either DPT or pentavalent vaccine.

Children also receive the rotavirus and pneumococcal vaccines at six weeks of age. These vaccines were added to the UIP nationwide only in 2019, so the coverage for rotavirus remains low at about 44%.

Booster dose and drop-out rates

Booster doses for polio, DPT (or pentavalent) and other vaccines are given at 10 and 14 weeks.

Vaccines work by training the immune system to recognise and fight disease without causing the illness itself. The first dose often primes the immune system-it introduces the body to the pathogen so the immune cells start recognising it and produce antibodies to fight it. However, this initial exposure does not always create strong or lasting protection on its own. Protection from the initial dose or primary series may weaken over time. Booster doses help strengthen and extend the protection, keeping the immune system ready to fight off infections.[15]

This is important not just for individuals, but for entire communities. When a large share of children are fully vaccinated, herd immunity develops. This means the disease finds it harder to spread, which protects even those who are too young or too ill to be vaccinated.[16]

Drop-out rates, or the share of children who receive the first dose but do not go on to complete the series, also point to deeper gaps in the system. They indicate that families who are able to access vaccination services at least once, most often at birth in case of institutional deliveries, may struggle to return for routine doses.[17]

For instance, in the case of polio, about one in ten children who receive the first routine dose do not go on to complete all the required oral polio vaccine doses. For DPT, drop-out rates are lower, around 7% of children who receive the first dose do not receive the third. Globally, the DPT drop-out rate is used as a key indicator of how well an immunisation programme is functioning. It reflects a system's ability not just to reach children once, but to ensure they complete the full schedule needed for protection against vaccine-preventable diseases.

The World Health Organization recommends that this drop-out rate should be below 10%.[18] India crossed this milestone for the first time in 2021, marking an important improvement in the reach and continuity of the immunisation programme.

Additional vaccines and booster doses are given between nine months and two years of age. These include the measles-rubella vaccine, which has a coverage of about 88%, as well as booster doses for polio and DPT (or pentavalent). In selected states children also receive the Japanese encephalitis vaccine.[19]

How coverage has changed by vaccine

The Universal Immunisation Programme (UIP), launched in the 1980s, initially focused on a core set of vaccines - BCG, DPT, oral polio vaccine (OPV), and measles. Over the years, newer vaccines such as pentavalent, rotavirus, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and others have been added. Looking at individual vaccines over time shows the scale of progress more clearly. We track BCG, DPT, polio, and measles vaccines, for which comparable NFHS data is available from the early 1990s.

Polio vaccination given at birth shows one of the most dramatic changes in recent years. Only about 3% of children received it in 1993. Because polio is highly infectious, spreads through contaminated water, and can cause permanent paralysis, the government launched the Pulse Polio Programme in 1995.[20] As a result, coverage of the birth dose rose to about 85% by 2021.

Other vaccines have also seen steady gains. Over the same period, coverage of BCG, first dose of polio as well as DPT rose from under seven in ten one-year-olds to more than nine in ten. Measles coverage doubled between 1993 and 2021.[21]

[1] Immunization and Child Health, UNICEF.

[2] A brief history of vaccines & vaccination in India (2014), C. Lahariya, Indian Journal of Medical Research.

[3] Universal Immunization Program, MoHFW.

[4] Zero Case India Polio Eradication Saga, MoHFW.

[5] Why childhood immunization schedules matter, WHO.

[6] Children aged 12-23 months are considered vaccinated if they received the following vaccines at any time before the survey, based on information from a vaccination card or the mother's report: one dose of the BCG vaccine, three doses of the DPT vaccine, three doses of the polio vaccine (excluding OPV given at birth) and one dose of the measles vaccine. National Family Health Survey (2019-21), IIPS.

[7] The Global Health Observatory, World Health Organization.

[8] Vaccine efficacy, effectiveness and protection, WHO.

[9] National Family health Survey (1992-93), IIPS.

[10] World Development Indicator, World Bank.

[11] Principles and considerations for adding a vaccine to a national immunization programme, WHO.

[12] Code of practice, National Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation, MoHFW.

[13] National Immunization Schedule, MoHFW.

[15] Vaccine efficacy, effectiveness and protection, WHO.

[16] Vaccine efficacy, effectiveness and protection, WHO.

[17] Exploring the Pattern of Immunization Dropout among Children in India: A District-Level Comparative Analysis (2023), P Dhalaria et al, Vaccines.

[18] Global Routine Immunization Strategies and Practices, WHO.

[19] National Immunization Schedule, MoHFW.

[20] Zero Case: India's Polio Eradication Saga, MoHFW.

[21] This analysis uses data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), which in its first round collected information only on BCG, DPT, polio, and measles. As India's immunisation programme expanded, later NFHS rounds added newer vaccines to the survey. NFHS-4 began collecting data on hepatitis B, while NFHS-5 includes information on BCG, hepatitis B, pentavalent or DPT, polio or OPV, rotavirus vaccine and measles or measles-rubella vaccines.