The Total Fertility Rate - a key demographic indicator that estimates the average number of children that a woman will have in her lifetime - has dropped to 1.9 children per woman on average in India as of 2023.[1]

When a country's Total Fertility Rate (TFR) drops to 2.1, meaning that a woman is expected to have 2.1 children on average over her lifetime, demographers say that the country has reached 'replacement fertility'. This is a key milestone in a country's demographic journey, and is a fertility level that indicates that the population will stop growing larger after some time, and will only replace itself.[2] If fertility falls further below that level, as it has in India, the population will over time begin to decline in absolute numbers.

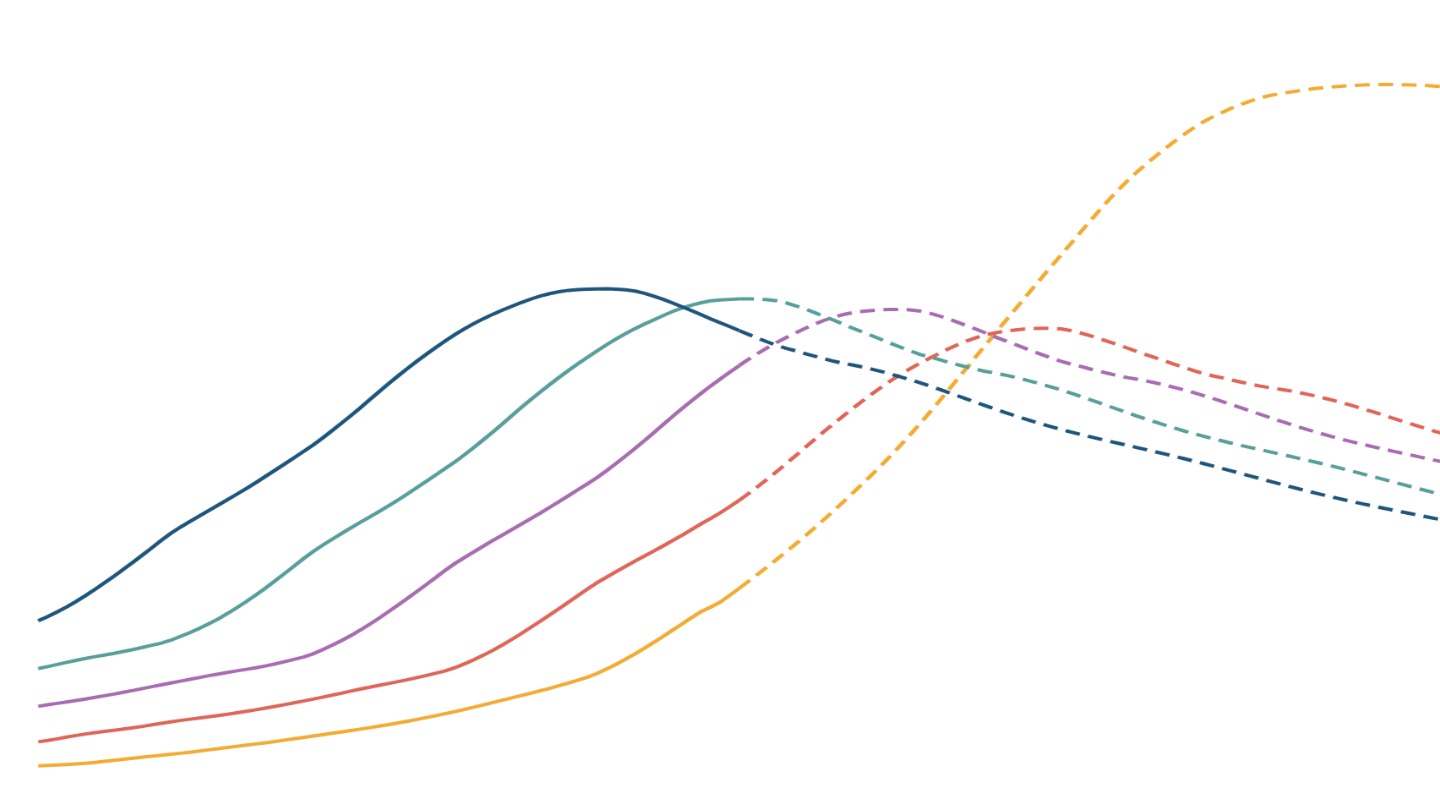

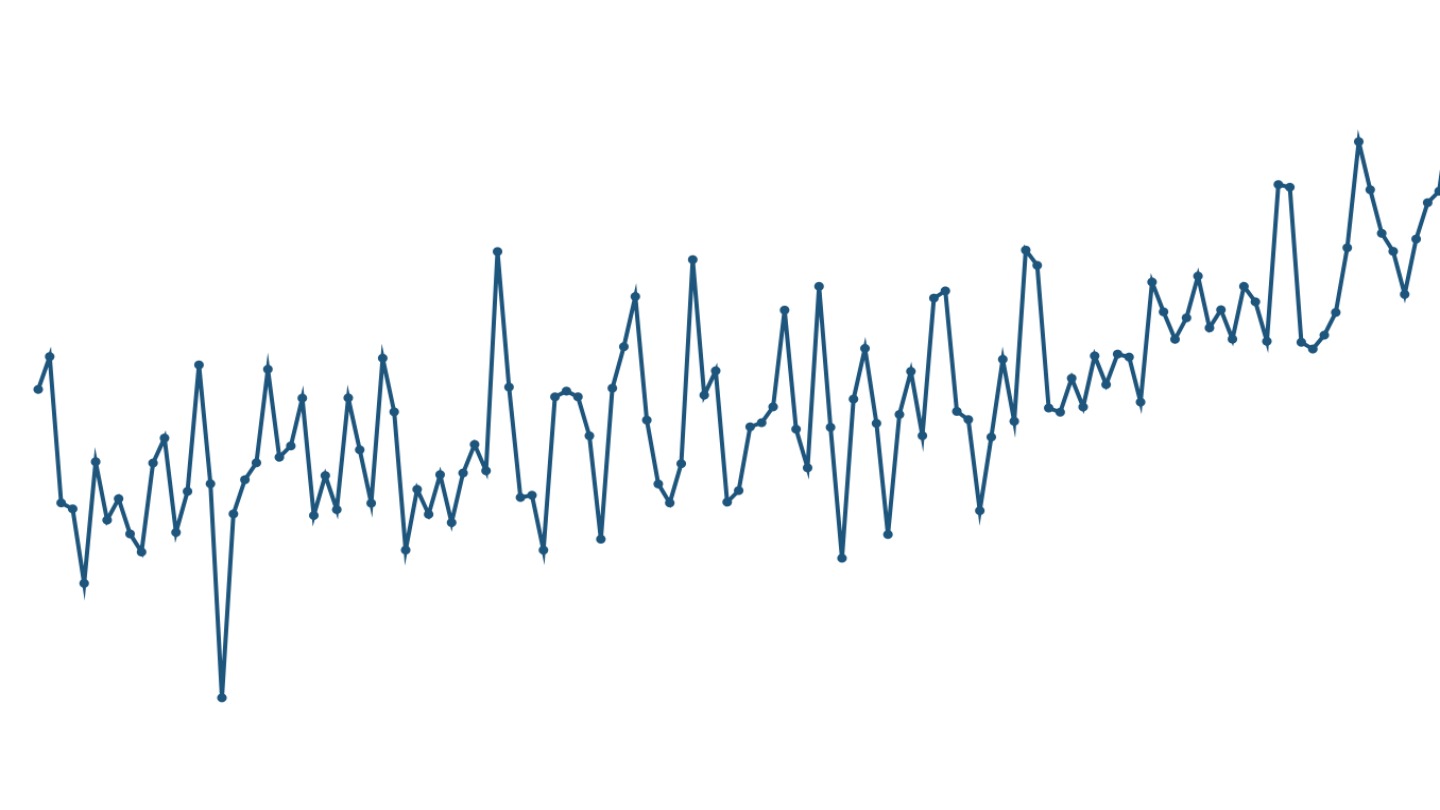

After being high in the early decades after Independence, India's TFR has fallen rapidly. India's fertility rate is now far lower than the Sub-Saharan countries that it was comparable with in the 1950s, and has fallen below the world average.

Regional trends

The fertility rate is higher in rural than in urban India. By Indian estimates, TFR fell below replacement in 2019, with TFR in urban India reaching this milestone much earlier in 2004. TFR in rural India is also estimated to have fallen below replacement as of 2023, the most recent year for which official Indian data is available.

Some Indian states have been living with fertility rates that are as low as in parts of the developed world for several decades now.

Kerala was the first Indian state to reach replacement fertility in 1988, when the national TFR was still 4. Tamil Nadu followed five years later in 1993, and Andhra Pradesh a decade after Tamil Nadu in 2004. West Bengal in India's east is an outlier in terms of fertility - despite being one of India's poorest states, the state reached replacement fertility in 2005.

Four Indian states are yet to reach replacement fertility, and all of them lie in India's centre and north. By 2023, the most recent year for which there is data, Chhattisgarh had not yet achieved replacement fertility despite the projections for the state estimating that it would reach this milestone in 2022. Uttar Pradesh is projected to reach this milestone in 2025 and Madhya Pradesh by 2028. Bihar is expected to be the last state to achieve replacement fertility in 2039.

Across the southern and western states, TFR is well below replacement level. In these states, levels of fertility are as low as in countries in the developed world. Maharashtra's fertility rate, for instance, is lower than that of Norway.

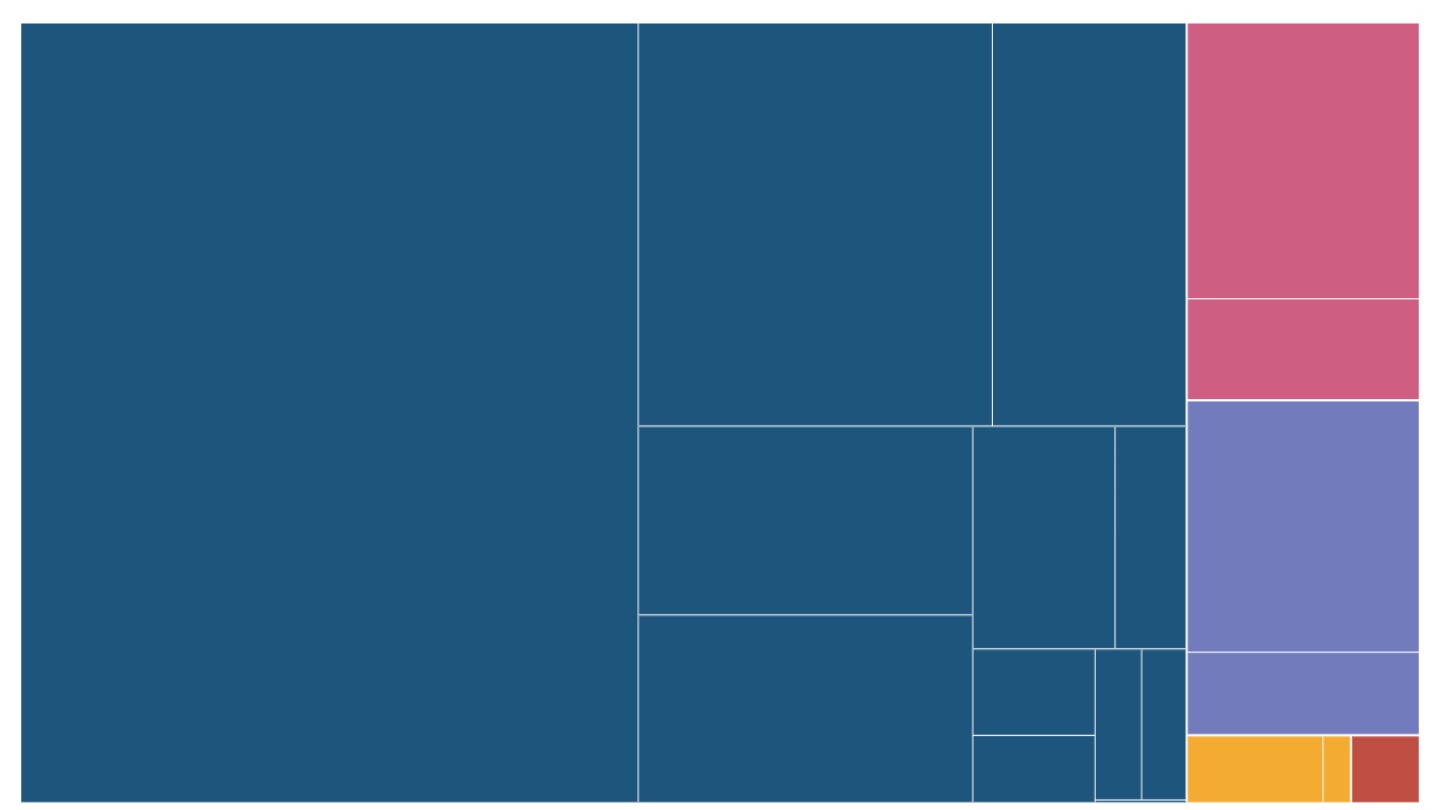

Across the world, TFR is higher among poorer and less educated groups, and then falls over time as those groups get richer and better educated. In India too, TFR was highest among the poorest 20% of Indian households, where the average woman had an estimated one child more than the average woman in the richest 20% of households.[3] The gap between less and more educated women is similar: women with no schooling have an average of one child more than women with 12 or more years of schooling. However, over time, TFR has fallen in both richer and poorer households, and among women with more and less education.

Age at childbirth

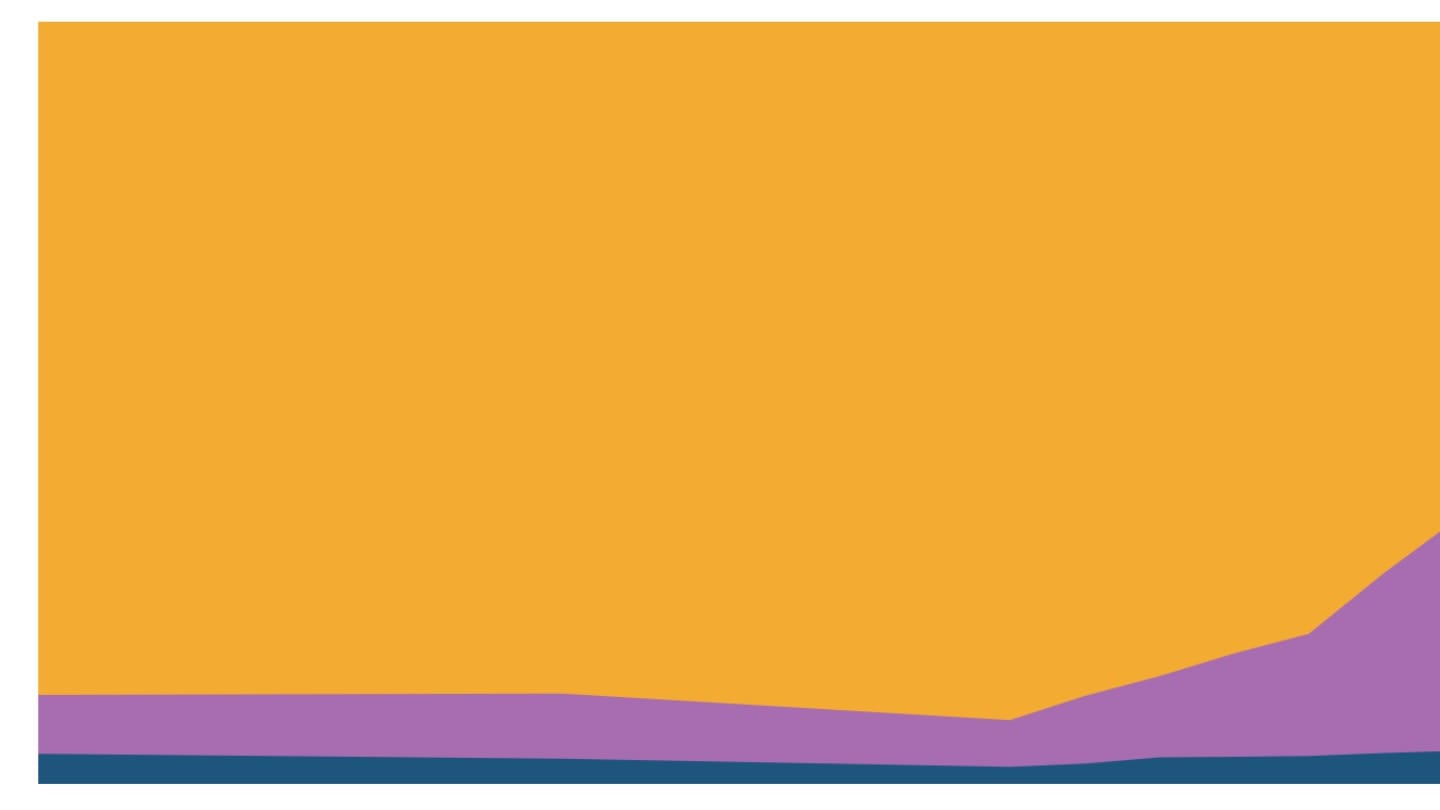

In most of the developed world, falling fertility manifests as women having fewer children, later in life. In India, however, falling fertility plays out in the form of women continuing to have their children relatively early, but then stopping after two children and not having more later in life.

Over the past two decades, the age at which women have their first child has grown only slightly, by less than two years; the median Indian mother now has her first child at just over 21 years. This tracks closely with changes in the age at which Indian women get married, which is just over 18 years.

What has changed significantly, however, is the age at which women have their last child. As families become smaller, more women are completing all their pregnancies in their twenties. As a result, the median age at which an Indian mother has her last child has fallen more substantially, by more than five years.

Across the world, as incomes and access to education rise, women begin to marry slightly later and have children later. While this is taking place in India as well, the majority of births every year in India are still to women who are in their twenties, as compared to, for example, the United Kingdom where women now have their first child much later, and most births are now to women in their thirties.

However, the change in India is apparent as well. Since the 1950s, the majority of births every year in India have been to women in their early twenties. The United Nations' population estimates suggest that this likely changed in the last few years, and that the largest share of annual births in India is now to women in their late twenties. (See more in our work on mothers' age at childbirth.)

Why is fertility falling in India and in the world?

In their 2025 book, After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People, economists Dean Spears and Michael Geruso assemble high quality data from across the world to understand why fertility really is falling.[4] In North America and Europe, the opportunity costs for women who temporarily or permanently withdraw from the workforce to have children are substantial and demonstrable, Spears and Geruso argue, and this is often advanced as an explanation for falling fertility. However this theory does not hold for India.

Most adult women in India don't work for pay outside the home, while most women in East Asia or Europe do. Yet, birth rates in India are comparable to those in Viet Nam now, for example.

The age at which women have their children is also lower in India than in East Asia, North America or Europe, meaning that women delaying childbirth for their careers is also not an explanation for falling fertility here.

Why then are birth rates falling in India and elsewhere? Spears and Geruso argue against a grand theory and make the case that there is much that we do not know about low birth rates. Instead, they suggest that the world has got better in many different small and big ways that make the opportunity cost of having children too great. These include both economic opportunity costs, but also the preference for more leisure, and other intangibles - simply put, the growing pleasures of having more time to do more of the nice things that people would like to do.

Changing this is not easy. State control - coercive actions or incentives to either lower or raise birth rates - have not been successful in the long term anywhere in the world, Spears and Geruso argue.

What is the future of fertility in India?

The United Nations Population Division publishes a revision to its World Population Prospects every two years. Its most recent revision in 2024 suggests that India's fertility rate will now fall gradually for the next 75 years for which the UN has made projections. At the projected rates of fertility and mortality, India's population is expected to decline in absolute terms from 2060 onwards.

This is similar to UN projections for other countries, where the estimates are broadly for fertility to decline only slowly over the next 75 years and to remain at roughly between 1.5 and 2. South Korea is one of the only countries in the world where TFR is now below 1; here the UN estimates that TFR will rebound slightly to rise over 1, and then remain so for the rest of this century.

However, fertility could continue to fall lower than the UN's current estimates. India's own population projections are dated as a result of having been made off the 2011 Census. These projections suggest that by 2035, at least seven major Indian states, including Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Punjab and Jammu & Kashmir will have a TFR of 1.5. These projections are also likely to be under-estimates - the TFR of states like Bihar was, by 2023, already significantly lower than the 2011 projections.

[1] Sample Registration System annual Statistical reports, Registrar General of India.

[2] The crude explanation is that if two adults have 2.1 children between them, then accounting for childhood and adolescent mortality rates, that couple will produce two adults, and the size of the population will remain the same.

[3] National Family Health Survey 5, 2019-21, International Institute for Population Sciences.

[4] After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People (2025), Dean Spears and Michael Geruso, Simon & Schuster