The full extent of people's interactions with the law in India can be difficult to quantify.

India's National Crime Records Bureau publishes annual statistics on the number of offences registered every year under various criminal laws, as well as the share of these reported crimes that were sent to courts. However, this is an incomplete repository[1], and no analogous record exists for civil laws.

To go beyond the limitations of police-recorded data, researchers often turn to data from India's courts to understand the full landscape of people's interaction with the law. In this piece we look at court data from ten years to understand the nature of these interactions through the most widely used civil and criminal acts and the Sections that people had turned to for redressal or had cases filed against them under.

With the exception of constitutional law cases and a relatively small number of other cases, legal disputes are first heard at subordinate courts. These courts, which hear both civil and criminal matters, function at the level of the district and sometimes, sub-divisions of a district. A dataset of cases heard by these courts, as a result, covers a much wider landscape of all civil provisions used and criminal offences registered in the country than other datasets are able to capture.

About the data

Subordinate courts function under the supervision of any of the 688 district courts.[2] Our dataset includes all cases that were disposed of[3] at the level of a district, including those before magistrates, civil judges and the district and sessions judges, across every subordinate court, between 2010 and 2020.[4] This data was scraped from India's official e-courts portal by a team of researchers at the Development Data Lab, and is a public dataset.[5] Each entry includes the case number, case type, hearing dates, date of disposal, name of the parties in the case, the designation of the judge, outcomes and the Act name and the Section number.[6]

For the purposes of this analysis, we considered only those cases which had been disposed of during the time period of 2010-2020, and excluded cases that were still pending.[7] For each case, the dataset records the Acts and Sections under which the case was filed. One case may be recorded with several Acts and Sections. For our analysis, we excluded the two main procedural codes: the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (CPC) and the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC), which are essential to every case, but do not by themselves tell us what the nature of the case was.[8] We also excluded Act names that had a small number of entries.

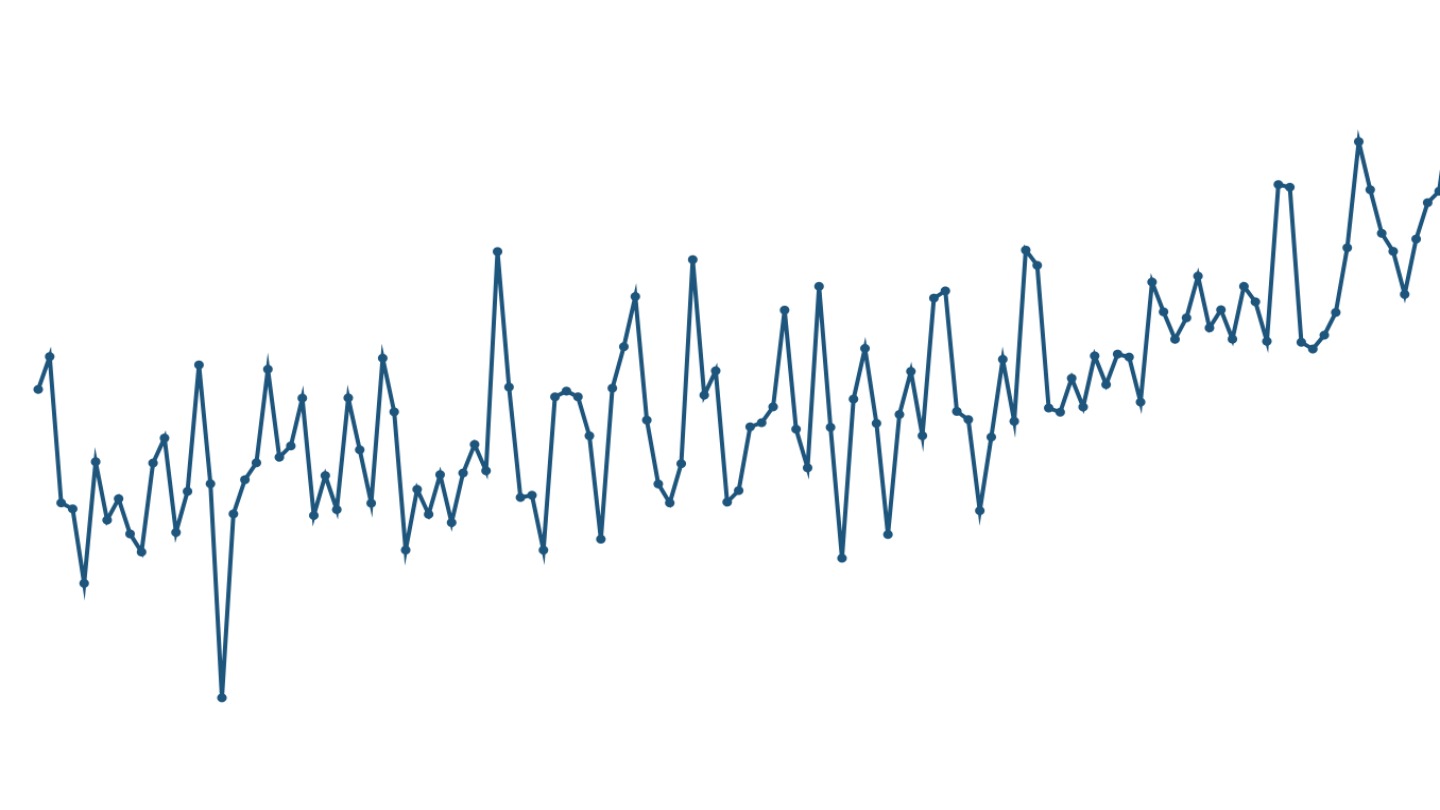

This has left us with a set of over 43 million records for legislation that have been invoked in cases. Any reference to "the dataset" in this piece refers to this set of 43.6 million records.[9] On average, over 3.6 million cases were filed annually, and the distribution of cases under different legal Acts and Sections follows the same trend.

Given the lack of uniformity in the way legislation names are stored, with different spellings, abbreviations (for example, the law is spelt as 'Indian Penal Code', 'IPC', 'I.P.C.' and in a number of other variations), we aimed to clean up and standardise names for only the most frequently invoked laws. We must also note that there are data entry errors in the e-courts database that we observed through manual checks; wherever we noted these, we have mentioned them. As a result, while this is a more expanded dataset than many other available official sources for quantitative legal data in India, it is neither complete nor completely reliable.

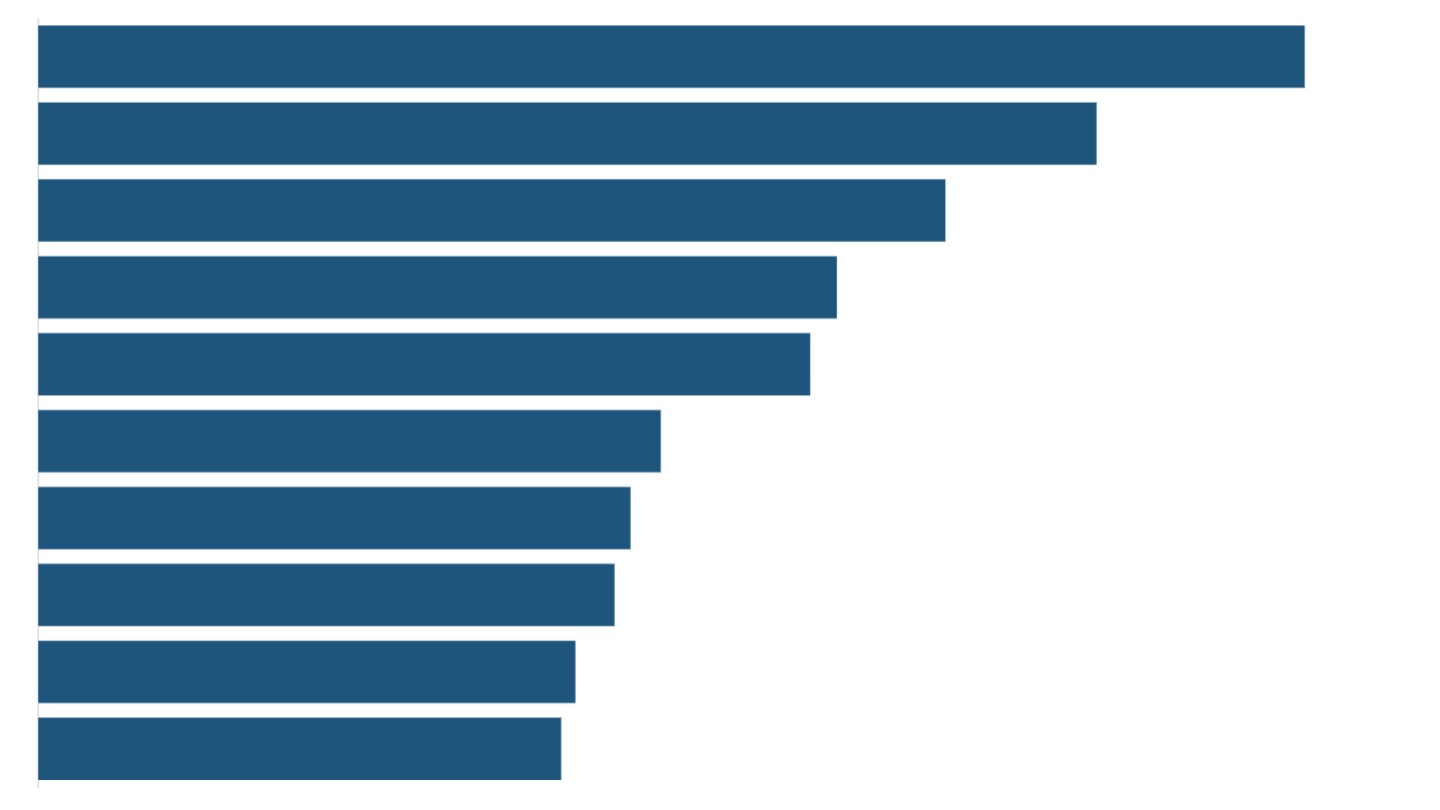

For this piece, we focus on cases under the top ten legislations overall. A majority of the cases in India's subordinate courts appear to have been filed under a small subset of substantive laws. Over 80% of the 43 million records could be categorised into ten Acts or groups of Acts.

Civil and criminal laws

Laws are typically either criminal or civil. Criminal laws define criminal offences, which is a behaviour considered to be harmful to the society at large and for which the right to prosecute and punish is given to the State. Criminal laws lead to court proceedings typically starting with a First Information Report (FIR) registered by the police or a private complaint before a magistrate, and end in an acquittal, or a conviction and punishment. In contrast, civil laws define civil wrongs, create rights and obligations between private individuals and provide remedies for the disputes to be resolved between the parties, including restitution, fulfilling obligations and monetary benefits instead of a punishment by the State. These are adjudicated by a process, governed by its own set of procedures and rules of evidence.

The top ten statutes for this analysis includes two civil statutes (Hindu Marriage Act, and the Registration of Births and Deaths Act) and seven criminal statutes (Indian Penal Code, Negotiable Instruments Act, Police Acts, Excise Acts, Prohibition Acts, Electricity Act and Railways Act). Since many states enforce their own Police Acts, we have combined state Acts and the central Act for our analysis. Since many states have their own Excise Acts and Prohibition Acts, the numbers under the state excise and prohibition legislations have been combined together into two different groups respectively.

There are also laws that contain provisions of both criminal and civil nature. The Motor Vehicles Act of 1988 is one such Act containing both criminal offences and a handful of civil provisions in use when a person wants to make a monetary claim for an accident.

Within the data under the top ten Acts, the vast majority (89%) was under criminal statutes with the rest being classified into civil statutes. This skew towards criminal laws is on account of a number of reasons. For one, many civil cases including many property matters are filed under the Code of Civil Procedure, which we excluded from our analysis. Secondly, cases under the Companies Act, which could account for a large number of civil cases, are filed before the National Company Law Tribunals and this data is not part of this dataset. Finally, data from other sources also confirm that more criminal cases are filed in courts, and are slower to be disposed of.[10]

We look at the five most commonly invoked criminal laws and the five most commonly invoked civil laws more closely, as well as the most widely invoked Sections under each of these laws, to present a snapshot of the most widely observed violations of law.

Criminal Laws

A criminal case usually commences when the police registers an First Information Report (FIR). This report is forwarded to the magistrate, while the police commences its investigation. In other cases, a criminal case is instituted when a complainant files a complaint before the magistrate.[11] When an Act and a Section are invoked in the record of a criminal case, it would imply that the provision was cited either by the police in the FIR or by the complainant in their private complaint.

The Indian Penal Code (IPC), the main criminal legislation in the country before it was replaced by Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) in 2024, made up over a third of the entire dataset. Together with the Motor Vehicles Act of 1988, the Negotiable Instruments Act of 1881, a cluster of Police Acts and a cluster of state Excise Acts, the IPC represents over 64% of the entire dataset.

1. The Indian Penal Code (IPC) (1860)

The Indian Penal Code was the primary criminal legislation in the country from 1860 to 2024 when it was replaced by Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita.[12] The IPC both defines what constitutes an offence and stipulates the punishment for it. Offences under IPC are divided in chapters such as "offences against the human body", "offences against property", "offences affecting public health, safety, convenience, decency and morals", among others.

Within the IPC, Section 279 (rash driving or riding on a public way) is the most frequently invoked offence. It accounts for 1.91 million records, or over 13% of all the times IPC was invoked, and over 4% of the entire dataset.

The offence of rash driving is followed by Section 323 (punishment for voluntarily causing hurt), Section 379 (punishment for theft), Section 506 (punishment for criminal intimidation) and Section 504 (intentional insult with intent to provoke breach of the peace). All together the five Sections make up over 41% of all the times an IPC Section was cited.

Notably, all five by themselves are petty and non-serious offences, for which the law prescribes that arrests should not be made unless most necessary,[13] and the punishments for these range from an imprisonment of six months and/or a fine (Section 279) to an imprisonment of three years and/or a fine (Section 379).[14] All of these offences also allow 'summary trials' which are proceedings with less stringent rules of procedure allowing for their faster disposal. For example, in case of theft, a summary trial can be allowed when the amount stolen is worth Rs. 200 or less.

2. Motor Vehicles Act (1988) [Criminal Provisions]

The Motor Vehicles Act is a central legislation that regulates different aspects of road transport and traffic.[15] Here, we look at those Sections in the Act that cover various conditions with respect to owning and using a vehicle including its registration, licenses and safety prescriptions. The outcomes of violating these conditions are essentially a criminal process involving the Traffic Police and the magistrate.[16]

Within the MV Act, Section 177, a general provision for certain offences under the Act such as disobeying traffic signs or driving without registration has the highest frequency of citation. Following this, Section 185 (driving by a drunken person or by a person under the influence of drugs), Section 181 (driving vehicle without a license or when underage), Section 184 (driving dangerously) and Section 192 (using vehicle without registration) are the four next most frequent criminal provisions.

These are also petty or non-serious offences, and carry penalties ranging from a mere fine of Rs. 100 in case of Section 177, to an imprisonment of not more than two years in case of a repeat conviction under Section 184 and 185. Section 192-using a vehicle without registration-carries a maximum fine of Rs. 10,000. When they do go to courts, procedure under the MV Act allows these cases to be disposed of through a shorter and simplified procedure of a summary trial.

3. Negotiable Instruments Act (1881)

Section 138, which is 'dishonour of cheque for insufficiency, etc., of funds in the account', or what is known as cheque bouncing, is the sole criminal offence under the Negotiable Instrument Act. It is punishable by an imprisonment for a period of up to two years and a fine of up to twice the amount of the cheque. At 2.8 million, Section 138 of NI Act is the single most common legal provision in this database; nearly a million more than the next most common provision: Section 279 of IPC. Section 138 alone represents over 6% of the entire dataset.

The procedure with respect to Section 138 is different from other criminal provisions: while most other offences are registered by the police and presented before the court by a prosecution, a case under Section 138 of NI Act can only be initiated by the payee or the holder of the cheque by a complaint filed before the magistrate. As a result, the high volume of cases under Section 138 and their conviction and acquittal rates do not get reported in annual statistics published by the police, despite the fact that the police are involved.

The process is supposed to be expeditious and the offence is 'compoundable' which means parties can settle the matter between themselves and the case is therefore withdrawn. However, in practice these are rarely expeditiously resolved and the backlog of cases under Section 138 has vexed the central government and the higher judiciary for several years. The criminal offence was added to the law only in 1988, however there have been several amendments to procedural aspects of the law over the years to address the backlog and the delays. The Supreme Court has also on occasions tried to address the problem. Most recently, in September 2025, noting the fact that the difficulty in serving summons to the accused is the main cause of the delay in disposal of these cases, it issued guidelines encompassing things like electronic means of serving summons and making payments, formats for filing complaints and better monitoring of cases in District Courts and High Courts in Delhi, Mumbai and Kolkata.[17]

4. Police Acts

Police Acts represent the fourth largest share in the database. For the purpose of our analysis, we have included the central Police Act of 1861 alongside state-specific acts such as Bombay Police Act of 1951 (applicable in both Maharashtra and Gujarat), the Karnataka Police Act of 1963 and Kerala Police Act of 2011 in this category.

Most of the Sections cited are offences that fall in the domain of the police's order-maintenance functions, covering behaviour on streets or otherwise in public that cause nuisance or inconvenience to others. Section 34 of the central Police Act of 1861 ("punishment for certain offences on roads"), for instance criminalises certain acts when they are done on public roads and cause trouble to others. These include slaughtering of animals, obstructing passengers, selling goods, throwing rubbish, or being drunk on the road, when they cause obstruction, inconvenience, annoyance, risk, danger or damage to people.

Section 92 of the Karnataka Police Act of 1963 includes obstructing roads and footpaths, use of loudspeaker between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m., public urination and indecent exposure, and using threatening words on the street to breach peace, among others, as street offences. Sections 118 of the Kerala Police Act of 2011, and Section 102 of the Bombay Police Act of 1951 (applicable in both Maharashtra and Gujarat), both broadly cover the same subject matter with some additions and subtractions. Provisions in the state Police Acts of Karnataka, Maharashtra and Gujarat that are most commonly used carry only a fine, whereas Section 34 of the central Police Act carries a maximum jail time of eight days, and Section 118 of the Kerala Act carries a maximum sentence of three years.

5. Excise Acts

Excise Acts represent a group of state legislations meant to regulate trade of intoxicating substances including alcohol. These laws typically allow taxes to be levied on lawful production and distribution, and also prohibit their unlawful production, distribution and use. Often the ban is extended to even possession and consumption of unlawfully produced goods or goods beyond a prohibited limit. State excise legislations from Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Kerala, Bihar and Odisha contribute to large slices in the category of Excise Acts. Notably, this data for Bihar is primarily for a period from 2010 up to 2016 when the state passed the Bihar Prohibition and Excise Act of 2016, completely banning the manufacture and sale of alcohol. This 2016 as well as the Gujarat Prohibition Act, 1949 have been excluded from the category of Excise Acts as they are targeted at the complete prohibition of intoxicants instead of taxation.[18]

The most commonly used provisions across state acts in the above states are those that cover manufacture, sale, transport, import and possession of intoxicants, and to a lesser degree, their consumption and being found intoxicated in public. These mostly carry a punishment of a few months, and in some cases such as a repeat offence, up to five years of imprisonment.

Civil Laws

A civil statute typically has provisions that define rights and obligations of individuals with respect to relationships that they enter with each other, whether personal or contractual. The statute also provides remedies or reliefs to parties in case there is a dispute with respect to these rights and obligations. For example, if a party to a contract violates its terms, the other party can approach the court to order the violating party to perform what they had agreed upon, or for compensation. Similarly, during a marriage, if one spouse has been cruel to the other, the aggrieved spouse can file for divorce.[19]

The top five civil statutes- the civil provisions of the Motor Vehicles Act of 1988, the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955, the Registration of Births and Deaths Act of 1969, the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act of 2005, and the Arbitration and Conciliation Act of 1996- contribute only 11% of the full dataset.

1. Motor Vehicles Act (1988) [Civil Provisions]

While most of the provisions of the MV Act are criminal in nature, three chapters of the Act (Chapters X, XI and XII) pertain to civil processes. The MV Act creates civil judicial bodies called the Motor Accident Claims Tribunal (MACT), which hear all claims made that are civil in nature, meaning a claim made by a party against another party with respect to any loss of life or property or damage to vehicles. This includes claims with respect to the liability of insurance companies.

Section 166 of the MV Act creates this right to approach the MACT for compensation in case of an accident. This provision alone had been cited 1.25 million times, and was the most widely cited section within civil Acts.

2. Hindu Marriage Act (1955)

The most frequently invoked civil legislation is the Hindu Marriage Act. The HMA codifies personal law related to marriage, divorce and separation among Hindus. Section 13 that enumerates grounds for contested divorce makes up the largest share of the data under HMA followed by Section 13B (divorce by mutual consent). There are also a substantial number of occurrences of Section 9 (restitution of conjugal rights), a much disputed remedy allowing the court to order a person to resume cohabitating with their spouse.[20]

3. Registration of Births and Deaths Act (1969)

The only provision under this Act that is in courts covers procedure to register a birth or a death in case it has not been done within a year of its occurrence. In such cases, it can be registered only upon an order made by a Judicial Magistrate of the First Class. Presumably, the cases that cite this Act are instituted upon an application by a relative.

However, our analysis suggests that a large number of cases under this Act were misclassified. Karnataka contributes to the highest number of cases under this Act. When their orders were manually checked, cases appeared to be wrongly tagged under this Act in a large number of instances. Many such wrongly tagged cases were instead cases under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act.

4. Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act (2005)

The next most used law is the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act of 2005. Under Section 12 of PWDVA, applications can be made to the magistrate asking for any of the remedies under the Act, including for protection, access to marital home and monetary relief, among others. This was invoked nearly 196,000 times. The objective of enacting PWDVA was to provide a remedy to survivors of domestic violence other than that under criminal law, and thus the procedure under the Act is largely civil in nature.

5. Arbitration and Conciliation Act (1996)

The fifth most commonly invoked civil legislation is the Arbitration and Conciliation Act of 1996. This statute mainly concerns civil disputes, in particular, those contractual in nature. The ACA was enacted to allow for dispute resolution through alternative mechanisms. However, the law requires parties to approach civil courts in certain cases such as when a decision made in an arbitration proceeding requires enforcement, or compelling a party to adhere to the decision.

Within the ACA, Section 9 (interim measures), Section 36 (enforcement of arbitral award) and Section 34 (application for setting aside arbitral award) are three most invoked provisions.

(This project was supported by Prof. Anup Malani and the University of Chicago. Gale Andrews, Assistant Professor of Law at NALSAR University of Law, advised us on the legal and data aspects. Our thanks to the Development Data Lab team for their assistance with the dataset.)

[1] One of the reasons is that NCRB follows the principal-offence rule. This means that each case is recorded in the statistics only for the most serious offence cited in the First Information Report. As a result, all other offences that were also part of the case are undercounted.

The NCRB is also not a complete, continuous database, but an annual summary of data reported by individual police stations.

[2] In India's three-tier court system, the first rung includes the courts of law presided over by civil judges and magistrates as well as the Courts of District and Sessions Courts Judges at the level of a district (jointly referred to as trial or subordinate courts). Next come the High Courts at the level of a state (or in some cases, a cluster of states and Union Territories), which are usually located in state capitals. Finally, there is the Supreme Court of India at New Delhi. Various specialised forums, tribunals and appellate bodies are also part of the court system and exist in parallel.

[3] This includes cases disposed of for any reason, including those where there has been an acquittal or a conviction, a decision in favour of any party, where a person has died and the case has been abated, merged with another case, where the accused was discharged without a trial, where the case was withdrawn by a party or settled, etc.

[4] Prior to 2010, the data for many states on the e-courts platform was incomplete. From 2020-21, the workings of courts were severely affected by the pandemic. As a result, the 2010-2020 period is most representative. The Development Data Lab dataset is until 2018; the team shared data for the years 2018-2020 with Data For India.

[5] DDL Judicial Data Portal, Development Data Lab

[6] 'In-Group Bias in the Indian Judiciary: Evidence from 5 Million Criminal Cases' (2025), Elliott Ash et al, The Review of Economics and Statistics. available at

[7] The complete DDL dataset includes 112 million cases, including those that have not yet been disposed of.

[8] Both the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 and the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 mainly describe how courts are organised, their jurisdiction, powers. CrPC also provides procedures with respect to investigations by the police.

[9] These are 43 million records found in 33 million cases, as when one case had multiple legislations and Sections cited, each was recorded separately. For example, when a case said "IPC 323, 307", this created two records - "IPC Section 323" and "IPC Section 307".

[10] For example, over 11 million civil and 36.5 million criminal cases were pending in courts at the district level as of January 8, 2026, as per the National Judicial Data Grid dashboard.

[11] Such complaints, commonly referred to as "private complaints", can be filed directly before a magistrate if the police refuses to register a case, or when the offence is "non-cognizable", a class of offences for which the police cannot make an arrest without an order from the magistrate.

[12] However, BNS retained most of the offence definitions and punishments from the IPC.

[13] Section 41 of the Code of Criminal Procedure mandated that when an offence was punishable with imprisonment up to seven years, the police must record reasons in writing why the arrest was necessary.

[14] All but Section 279 and 379 are 'non-cognizable' which means the police can make an arrest only when the magistrate orders, and all but Section 379 are 'bailable' which means they allow the accused to be released on bail as a right from the police station itself.

[15] Section 166 of the MV Act pertains to civil remedies and has been dealt with in the section on civil laws.

[16] Chapters II to IX in their entirety, as well as a few Sections under Chapter XI cover various conditions with respect to owning and using a vehicle including its registration, licenses and safety prescriptions. The outcomes of violating these conditions are provided in Chapter XIII of the Act (Section 177 to Section 210). Sections under this chapter prescribe punishment for their violation and also some aspects of the criminal procedure with respect to these violations.

[17] Sanjabij Tari v. Kishore S. Borcar, 2025 SCC OnLine SC 2069.

[18] Gujarat Prohibition Act, 1949 along with the Bihar Prohibition and Excise Act of 2016, the Maharashtra Prohibition Act, 1949 and the Tamil Nadu Prohibition Act, 1937 were instead combined into the category of 'Prohibition Acts'.

[19] In our analysis of common Sections, we have counted only those provisions that create this right to approach the court to ask for a remedy or relief, though a case may have also cited other provisions in addition to these. We have also excluded provisions which ask for relief but in the interim, since these are also always in addition to the main relief sought.

[20] Restitution of conjugal rights is presently under a constitutional challenge before the Supreme Court. It has been argued that the provision violates the right to privacy and personal autonomy. It has been abolished in other countries and has also been challenged in India in the past.